Government funding legislation passed by Congress earlier this month is set to triple ICE’s budget by 2028.

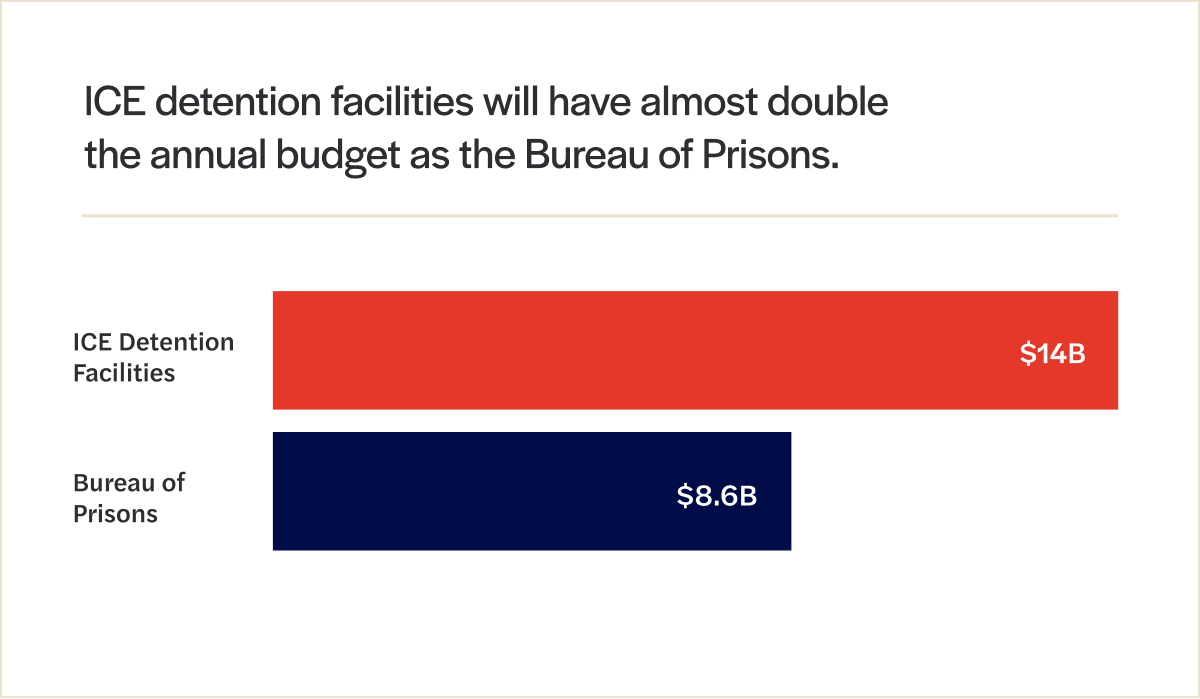

The new funding appropriated to ICE will bring their annual budget to $28 billion — making it larger than the budgets of the FBI, DEA, ATF, U.S. Marshals Service, and Bureau of Prisons combined. The yearly budget for ICE detention facilities alone will be nearly double that of the Bureau of Prisons.

It would be a mistake to view this expansion purely in immigration policy terms. This is not a change to American immigration policy. Instead, the expansion of ICE resembles something closer to the creation of a parallel carceral system accountable primarily to the president, and the president alone.

Two reasons why:

The current structure and practices of ICE make it functionally accountable only to the Executive Branch.

The vast majority of the resources provided by the new legislation are going to enforcement and detention without an equivalent increase in processing capacity through the immigration court system.

Together, these factors point to the possibility that ICE could become a large-scale, permanent apprehension and detention apparatus on the scale of or larger than the federal prison system and dwarfing other federal law enforcement agencies.

Expanding any law enforcement agency this quickly has consequences

Most of the new appropriations to ICE are earmarked for hiring new agents. A lot of them. Quickly. The funding is available to ICE through 2029, but it’s hard to imagine President Trump waiting until the end of his term to scale ICE into the mass enforcement machine that he envisions.

To understand why the accelerated timeline is important, I highly recommend journalist and historian Garrett Graff’s piece on previous examples of expanding an agency this quickly: Four fears about ICE, Trump's new masked monster.

What happens when a law enforcement agency at any level grows too rapidly is well-documented: Hiring standards fall, training is cut short, field training officers end up being too inexperienced to do the right training, and supervisors are too green to know how to enforce policies and procedures well.

Inevitably, corners are cut, mistakes are made, and people get hurt because the agency tried to scale too quickly.

ICE is fundamentally different from other federal law enforcement agencies

While previous law enforcement agency expansions can give us some sense of what might happen to ICE, it’s likely that ICE’s expansion will look dramatically different from other recent law enforcement expansions — because ICE itself is different from other federal law enforcement agencies:

The qualifications and training requirements for ICE agents are substantially less rigorous than those for FBI agents.

Unlike, say, the FBI, the current director of ICE is serving in an “acting” capacity and was appointed by President Trump without Senate approval. Acting directors avoid the political accountability of Senate confirmation. (ICE hasn’t had a Senate-confirmed director since the beginning of the first Trump administration.)

The president’s chief advisor on immigration policy is “border czar” Tom Homan, who was appointed by the president without Senate approval. Homan is a particularly aggressive deportation hardliner, saying he doesn’t “care what the judges think” in defiance of court orders halting deportations without due process.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem made significant cuts to the department’s internal oversight apparatus. Noem appears to have a disturbingly autocratic view of executive power, testifying before the Senate that habeas corpus is the president’s “constitutional right” to “remove people from this country.” (It’s not.)

While the new government funding legislation provides a $10 million funding increase for the Inspector General (IG) of the Department of Defense (the department’s chief watchdog), it does not increase funding for the DHS IG, despite the huge expansion of the department’s immigration enforcement capacity.

The current IG of DHS, an appointee of the first Trump administration, was found to have committed “substantial misconduct” by an independent oversight panel.

ICE has indicated they will rely on private prison contractors to increase their detention capacity. Doing so exacerbates existing concerns about corruption and accountability.

There are many other differences between the FBI and ICE, namely the FBI has much stricter rules of conduct.

We’ve already seen these differences in oversight and professionalism manifest themselves in ICE’s scaled up enforcement efforts. The administration itself has acknowledged facilitating erroneous deportations in defiance of court orders. ICE mistakenly detained a deputy U.S. marshal. A two-year-old American citizen was deported.

Then there are the structural differences. ICE is an executive branch agency, as is the immigration court system, which — unlike most courts — is housed under the DOJ. That means that both ICE agents and immigration judges report to the president, the attorney general, and DHS — and, reportedly, President Trump’s most powerful advisor, Stephen Miller.

This may all end with a massive and parallel prison system

At first glance, this funding increase could indicate an expansion of ICE operations across the board: More people will be detained and promptly deported.

But deportations require deportation orders from immigration judges. And the immigration court system has a massive backlog. (According to the DOJ, more than 3.8 million cases as of June 2025.)

The new legislation provides for a more than 300% increase in funding for ICE detention facilities and a 500% increase in funding for ICE’s “transportation and removal” budget.

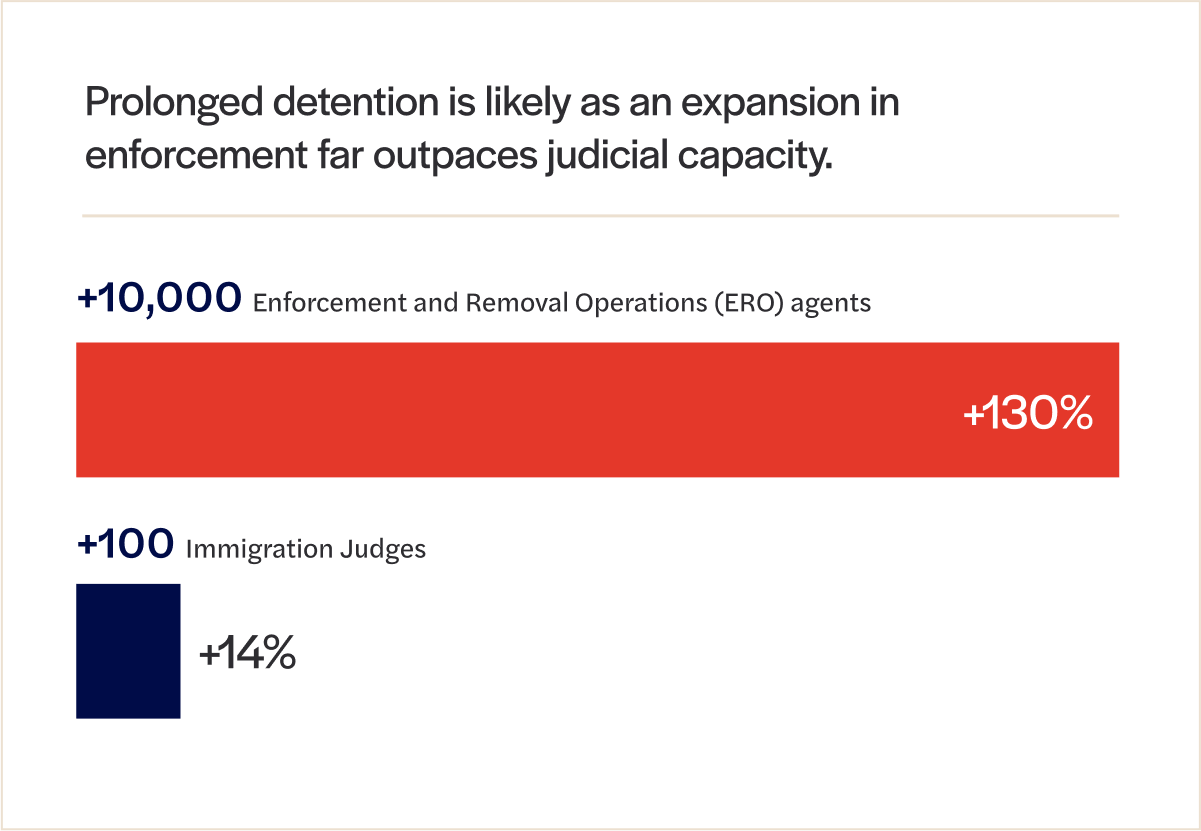

Simple math would suggest that if the administration really wants to increase deportations many times over, they would need to increase the capacity of the immigration court system by the same amount (or more). While the new budget does provide more funding for the Department of Justice’s immigration-related efforts, the increases are not proportionate to the increased resources for deportation efforts.

Adriel Orozco of the American Immigration Council put it this way:

Despite the bill’s enormous enforcement spending, less than 8% of the $170.7 billion funding will go to support immigration court processing… Rather than addressing [the backlog] through more judges or support staff, H.R. 1 caps the number of immigration judges at 800. This mismatch in funding priorities risks further entrenching delays and arbitrary outcomes.

Pause on that. Right now there are 700 judges. That means, while the bill more than doubled the number of ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations agents, it capped the number of immigration judges at only 14% more than the current amount.

Now, it’s true that this is still a large increase in funding for the immigration court system, and it’s possible it might begin to reduce the existing backlog.1 But without keeping pace with increases in deportation efforts, it’s hard to see how immigration courts will have enough resources to address the current backlog and process new cases in a timely manner.

So what happens next? If ICE can’t get deportation hearings for all the people who are detained, hundreds of thousands of detainees could remain in ICE custody “awaiting legal proceedings” but with little hope of a final ruling on whether they will be deported — potentially for many months or even years. (There are clear limitations on the amount of time someone can be detained without a bond hearing or after ICE gets a deportation order — 90 days per statute and 180 days according to a Supreme Court ruling — but it’s not clear what applies while they are awaiting a deportation hearing. There’s a mess of complex laws and legal precedents.)

Immigration law in this area is extremely complicated, and people detained by ICE do have some legal recourse to seek release (this primer from the American Immigration Council is a good summary). But in general, the process can be very time- and resource-consuming, and noncitizens can have a difficult time getting out of federal custody. For example, Rümeysa Öztürk and Mahmoud Khalil — both legal immigrants who had not been accused of any crime and had very strong First Amendment claims against their detentions — were detained for six and 15 weeks, respectively.

Even the many hundreds of thousands of noncitizens who are in the country legally and have not committed any crime — such as those here under Temporary Protected Status — could soon end up trapped in a sprawling immigration detention system with no apparent way out.

Meanwhile, as the immigration court backlog worsens, ICE will likely argue prolonged detentions are caused by immigration courts’ inability to keep pace, which they may conveniently claim is merely a logistical complication outside of ICE’s control.

Detainees out of sight and out of mind

To be sure, it’s not that President Trump doesn’t want to carry out the “single largest Mass Deportation Program in History.” It’s that deportations require a process — judges and hearings and evidence. It’s much easier to shout from the rooftops that you’re going to deport millions of people while, in truth, simply detaining them.

In the first six months of this administration, there has been a steady uptick in ICE detentions while deportation rates have remained mostly consistent. And when the White House has moved forward with more aggressive deportations, they’ve gotten into hot water with courts — and the court of public opinion.

Think about the cases you’ve heard about in the news. You could probably name some of the immigrants who’ve been deported: Kilmar Ábrego García, Andry Hernández Romero, Yenifer Correa Ganan, and many others. When the administration has rushed to deport people, the courts have ordered that the deportation isn’t lawful or that the person cannot be deported to a particular country. In some cases, judges have ordered the administration to turn around planes before deportations can be carried out or return people to the United States who have been wrongfully deported.

In turn, these cases have caused a public outcry and backlash against the administration, precipitating a decline in public approval of the president, particularly on the issue of immigration. In short, scaled-up deportation efforts have proved to be politically damaging.

But if his administration thinks it can hold more people in detention facilities (which the funding increase will make possible) without deportation hearings (thanks to the increasing overburdening of the immigration courts), they are less likely to get caught deporting the wrong people and less likely to have to defy court orders to get what they want.

Perhaps that explains why ICE, when confronted by politicians attempting to gain access to detention facilities to conduct oversight, is responding like this:

It seems like President Trump himself envisions ICE’s expanded detention efforts becoming a new prison system. When he visited “Alligator Alcatraz,” Trump said, "Well, I think I would like to see [similar ICE detention facilities] in many states. Really, many states. And, you know, at some point, they might morph into a system."

Let that sink in for a moment. The president is openly floating building a mass detention system under his direct and sole authority.

Columbia sets a dangerous precedent

On Wednesday, Columbia University announced that they had struck a “deal” with the Trump administration, opening up a specific department to what amounts to viewpoint-based monitoring and promising to reform the school’s "ideological balance" in exchange for federal funding.

Read more: Universities have no choice.

The White House’s strategy of coercing universities is a blatant abuse of power that undermines the independence and integrity of higher education. If institutions can be pressured financially to conform ideologically, the free exchange of ideas — critical to our democracy — is in danger. The federal government using its power to punish people who don’t share its views is contrary to our nation’s most basic values. And the attacks on Columbia are just the vanguard of a nationwide attack (see: Mapping federal funding cuts to U.S. colleges and universities). As a result, this capitulation threatens all of higher education nationwide.

Just as importantly, though, the deal is likely to prove naïve. If Trump's attacks on law firms are any indication, surrender is likely to only invite more extortion. University leadership may think that they have saved their funding, but as Columbia economist Suresh Naidu writes convincingly: Columbia’s administrators are fooling themselves.

[T]his deal is unlikely to end the attacks. The federal government, and this administration, is simply too powerful and too arbitrary to be credibly bargained with. Do we really think this arrangement, however destructive of academic autonomy it is, will prevent the Trump administration from stopping the money again?

What else we’re tracking:

Read this chilling piece from a former U.S. ambassador to Hungary: “After years watching Hungary suffocate under the weight of its democratic collapse, I came to understand that the real danger of a strongman isn’t his tactics; it’s how others, especially those with power, justify their acquiescence.”

The Bulwark’s Jonathan V. Last has an excellent piece on “the Surrender Trap,” the “hack built into the source code” of institutional liberalism that Trump exploits. Read the whole thing.

The people overseeing the Epstein case at DOJ are the president’s former personal lawyers. The potential conflicts of interest are enormous, argues Philip Rotner.

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights has a useful tracker of all the administration’s rights rollbacks across different issue areas.

In a different world, this interview with a DOJ whistleblower about government lawyers being asked to lie to the courts would be a presidency-defining scandal. Just because we no longer live in that world doesn’t mean you shouldn’t listen to the interview.

“Stop violating the law!” In an exasperated ruling, a court ordered the administration to stop covering up how it’s spending taxpayer money. Cerin Lindgrensavage explains the backstory: Court to OMB: Stop the cover-up.

On Pod Save America’s “Inside 2025” podcast, Ian Bassin and Kate Shaw talked about what lawyering should look like in the White House — and how the Trump administration has changed everything.

In case you missed it, Nathan Taylor Pemberton at The New York Times wrote recently about the cultural context of the Trump White House’s unique social media presence and the MAGA right’s proclivity for “Trolling Democracy.”

It’s worth noting that in 2023, the Congressional Research Service found that, to clear the backlog (which was about 1 million fewer cases then than now), the number of immigration judges would have to double — and it would still take until 2032. Previously, Republicans in Congress blocked a funding increase for immigration courts that the Biden administration requested in 2024. And when President Trump took office in 2025, he actually fired a number of judges.

I wish news and social media reporters would make more of direct connection to Auschwitz visually. The young need to know that this inhumane treatment by ice is very familiar to those who know the history of the holocaust. The visual of these cages of bunkbeds allways brings this to mind.

https://www.auschwitz.org/en/gallery/memorial/former-auschwitz-ii-birkenau-site/brick-barracks,11.html

Excellent review of the situation. Thank you. What can we do to stop it?