This week, America’s forever redistricting wars reached a new low — Texas Republicans and the White House are attempting an aggressive, mid-decade redraw of the state’s congressional map to try to keep the GOP in control of the House of Representatives in 2027.

In an attempt to deter Republicans — or at least mitigate the power grab — Democrats are responding however they can. Texas Democrats have fled the state to deny Republicans quorum, and blue state Democrats are threatening to redraw their maps to create as many safe Democratic districts as possible — including in states that have turned their redistricting process over to independent commissions to try to prevent gerrymandering, like California and New York.

These gerrymandering wars aren’t new — the term ‘gerrymander’ itself comes from a signer of the Declaration of Independence. And yet, even as 90 percent of Americans disapprove of politicians drawing districts to benefit themselves, there’s a reason why it’s so hard to kill: Our electoral system has a design choice that makes it uniquely vulnerable. That defect is the result of one law, the Uniform Congressional District Act of 1967 (UCDA), which requires states to draw single-member districts for the House of Representatives.

Single-member districts are easy to manipulate. It’s not hard for line-drawers to predict which party will have an advantage by packing a district with supporters, or by splitting up the opposition by drawing a line right through them. It’s no coincidence that countries with single-member districts are uniquely susceptible to gerrymandering. As one global study concluded:

Not all electoral systems are equally prone to gerrymandering. The problem is inherent in the system of one-seat districts.

Most modern democracies don’t have legislative districts represented by only one legislator — which is why most don’t struggle with gerrymandering like we do. Instead, a majority of democracies today use proportional multimember districts (we’ll get back to what this means in a bit), which makes gerrymandering “prohibitively difficult” in practice, in the words of that same study. Our decision to use single-member districts makes gerrymandering possible in the first place.

The good news is that our Constitution doesn’t require them. It’s a choice we’ve made. To understand why the gerrymandering wars persist — and to actually stop them — we need to get to the root cause. Yes, there are bad and better maps, and bad and better people to draw the lines. But under a single-member district system, gerrymandering is difficult to shake.

There are no perfect maps under single-member districts

Reformers have been trying for a long time to ensure fairer maps. But there is no such thing as a flawless one. When each district has one (and only one winner), those flaws are often very serious and practically impossible to avoid.

If we put aside the many states (like Texas) that aren’t even trying to draw fair maps and look only at good-faith redistricting efforts, even then the process can never be perfect.

As voters, we rightfully want lots of things from our electoral maps. Among others:

To be fair in partisan terms and not systematically advantage either party.

To represent distinct constituencies, especially racial groups, and ensure that they aren’t shut out of Congress.

To be competitive.

To be compact and logical in representing cities and neighborhoods.

To make elections administratively easier by following county lines and other political geography.

Accomplishing all of these, instead of just balancing between them, is an impossible task.

Even in the best-case scenario, single-member districts have to pick and choose between conflicting priorities. As Americans have geographically self-sorted into red and blue areas, creating competitive districts (when possible) requires contorted lines combining rural and urban areas. Maps that are “fair” in aggregate often look distorted up close. And since minority constituencies are rarely a majority in any specific geographic area, sometimes the only way to ensure representation is to intentionally draw non-compact districts, as the Voting Rights Act rightfully requires.

But here’s one of the biggest problems: Even if we got rid of gerrymandering, biased outcomes — the thing we really care about when we talk about gerrymandering — will persist as long as we have single-member districts.

For example, take a look at the two states that have virtually no gerrymandering, California and Massachusetts. California’s independent redistricting is often regarded as the “gold standard” of independent commissions. The commission is well-regarded by anti-gerrymandering advocates because it is composed of members of both major parties and unaffiliated commissioners, its members are citizens rather than elected officials, and the state legislature doesn’t have the power to override the lines drawn by the commission.

In California, though, while Democrats win about 60 percent of the vote statewide, they capture about 80 percent of congressional seats. If the commission has virtually eliminated gerrymandering — lines are not intentionally drawn to favor one party over another — why, then, do Democrats still have a dramatic advantage? It’s not because the commission is biased. Instead, the commission can’t eliminate bias because it’s constrained by other criteria — namely voting rights compliance, compactness, and the integrity of local communities of interest (i.e. making sure an entire town is represented by the same member of Congress).

(For an excellent conversation on the tradeoffs faced by independent commissions, we recommend this interview with Sara Sadhwani, one of the members of California’s commission.)

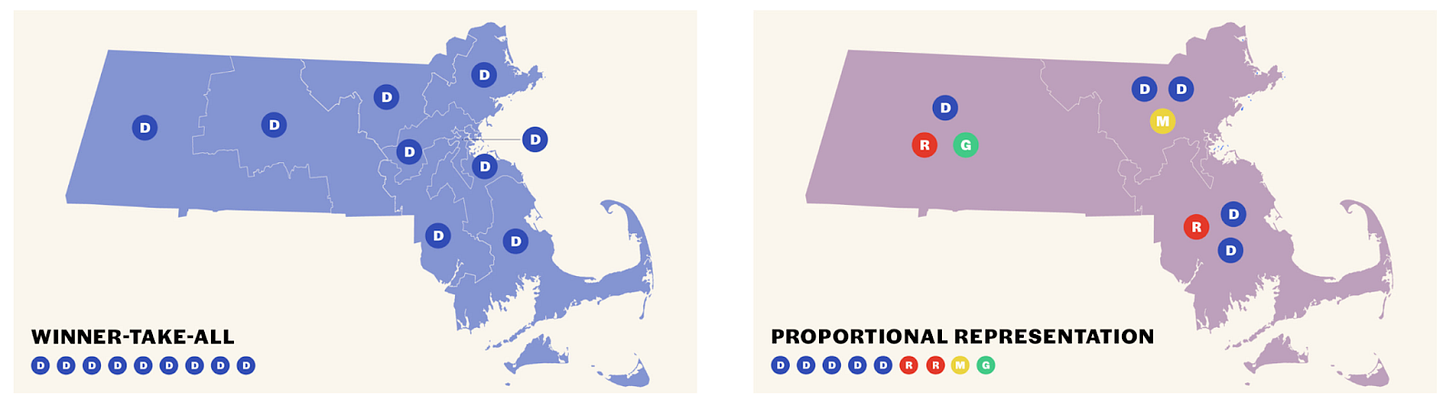

On the other side of the country, in Massachusetts, Republicans receive a little more than a third of the statewide vote, but of the state’s nine U.S. House seats, they win none. The cause isn’t gerrymandering; in fact, if anything, district lines in Massachusetts slightly favor Republicans. The problem is single-member districts. Republicans are too geographically dispersed across the state and don’t constitute a majority in any one district.

In fact, there is no possible map that would result in anything other than nine Democratic-leaning congressional districts. Seriously. It’s mathematically impossible — a group of mathematicians found that: “Though there are more ways of building a valid districting plan than there are particles in the galaxy, every single one of them would produce a 9–0 Democratic delegation.”

Read more: Why district lines matter more than our votes.

Even though independent commission-drawn maps are a substantial improvement on those drawn by politicians — and a national gerrymandering ban may be critical to stop the downward spiral — no redistricting process is going to draw perfectly fair maps.

Our single-member districts system leads to unrepresentative outcomes, stifles competition, and exacerbates polarization and extremism — in addition to setting the stage for intense redistricting fights and power grabs like we’re seeing this week.

The solution is simple and achievable

But there is a solution. A system that would end boundary-drawing brawls and make our democracy more effective, inclusive, and representative. It’s called proportional representation. How it works is intuitive: Share of votes equals share of seats.

Let’s go back to Massachusetts with its nine Democratic-leaning congressional districts. With proportional representation, if the vote share was 70%-30%, then Democrats would win about 70% of the seats, instead of all of them.

Under proportional representation, we can have it all. The same map can be competitive and fair, representative and compact. Racial minorities can be represented even when they don’t live in the same area. District lines can much more easily follow existing political and real-world geography.

Read more: Proportional Representation and the Voting Rights Act.

Plus, because it creates more competition and a more representative system, proportional representation opens the door for more politically viable parties, more coalition-building, and more cross-ideological allegiances. A more representative government with more incentives for compromise and moderation could also mean a more responsive, effective government.

For more, here’s Protect Democracy’s Farbod Faraji on how this all works:

And proportional systems are much harder, if not impossible, to gerrymander — because voters’ representation is based on how they vote, not where they live. It’s easy to make the opposition a minority in any given district. It’s impossible to draw them out entirely.

Even in the reddest and bluest parts in the country, at least one in five voters routinely vote for the other party. That’s enough for both sides to be represented everywhere.

Whether Republican voters in western Massachusetts are drawn into Massachusetts’ first or its second congressional district, they will still be represented by the same number of members of Congress because they represent the same percentage of voters in either district — even when they’re a minority.

Just as importantly, proportional representation isn’t a pie-in-the-sky dream. Because the constitution is silent on how many members may represent each district and how districts are drawn, Congress could amend the UCDA to require proportional representation. They could do it tomorrow, on a national level, through regular lawmaking. None of this requires a constitutional amendment. (Proportional representation can also be implemented on the state level through legislation or ballot initiatives — for example, see the ongoing effort in California.)

There has never been a better moment for ambitious reform

Obviously, this will not happen under the current Congress or president. And there are real and difficult questions around what pro-democracy actors need to do to prevent an authoritarian and his allies from using gerrymandering to seize power permanently. But if we really want to strengthen Americans’ commitment to democracy, we also have to work to make it better — not just preserve a flawed and outdated status quo.

Voters are increasingly disillusioned with our current two-party system — built around a zero-sum game of single-member districts — meaning the majority of Americans are hungrier than ever for systemic change.

But most people don’t know or understand that proportional representation is a simple, achievable option. That’s slowly starting to change, but it’s going to take your help. In the coming days, when people in your life or professional circles bring up what’s happening in the latest redistricting war, tell them that there’s a way out of this doom loop — proportional representation. Forward this piece to them.

And let us know how it goes in the comments.

The Orbán-ification of American elections

If you missed Wednesday’s case study on Hungary as part of our Democracy Atlas: Eight rules of antiauthoritarianism, it really is worth the time to read the story in full.

The White House seeking to change the midterm results long before anyone votes — by re-gerrymandering Texas and other states — comes straight out of Viktor Orbán’s strategy.

Here’s what the experience of pro-democracy leaders in Hungary teaches the United States:

Under an authoritarian government, every action is designed to cement the ruling party’s governing majority. The onslaught of changes to the electoral system — and society as a whole — may come quickly and be extreme. Do not waste time developing a perfect strategy.

In the first 6–12 months, prioritize resisting election system changes pushed by the ruling faction, since they are likely to further lock in uneven dynamics for political competition. NGOs that focus on elections can be a valuable watchdog. Work with them early on so changes do not go unnoticed. Spell out the risks of significantly modifying the election system so people are sensitized and equipped to oppose the changes.

Once the rules are set, however, be prepared to work within the new system and defend it from further harmful changes. Whenever possible, put in place (strict-as-possible) limits on the room for any last-minute procedural changes designed to advantage one side over the other, and have a backup plan if you fail to constrain them. Keep resources flowing to the opposition, aim for incremental wins, and continue to register voters — ideally in a way that prevents mass challenges to eligibility.

Read the whole case study: Rule One: Resist. Then adapt.

(Thankfully, there’s growing evidence that the opposition in the United States is adapting quicker than their Hungarian counterparts did. Talking Points Memo’s Josh Marshall explains.)

What else we’re tracking:

This week marks the 60th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act. And yet, even as we celebrate the law’s transformative impact on American democracy, profound new threats are brewing — from the Trump administration, from state governments, and from the Supreme Court. NPR’s Hansi Lo Wang reports. (For the record, Congress can and should pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act).

Reuters reports on a chilling escalation: Pro-Trump group wages campaign to purge “subversive” federal workers.

“This isn’t the first time the BLS commissioner aroused presidential ire. But at least Nixon faced constraints,” writes Tim Naftali in The Atlantic.

Midsize businesses face $82 billion tariff tab: New research from JPMorganChase indicates that the Trump administration’s overreach and abuse of emergency powers to institute sweeping tariffs will have real consequences for the business community.

A new pro-democracy organization called the Washington Litigation Group has joined the fight against authoritarianism, filling the gaps left by Big Law’s capitulation to the administration: New firm seeks to confront Trump on executive power.

One through line through many of Trump’s actions: Information, and control over it. Brian Stelter explains.

On a lighter note, from Sarah Beckerman in Waging Nonviolence: What fantasy stories teach us about defeating authoritarianism.

How you can help:

Do you own a small business? Do you want to be a part of the fight against authoritarianism? Anna Dorman has an opportunity for you:

Calling all small business owners! Integrity Matters is a fantastic non-partisan coalition of business leaders committed to defending democracy and the rule of law in the U.S.

They are currently collecting stories about how the tariff policy whiplash, politically motivated contract terminations, corruption and favoritism, and suppression of dissent undermine American small businesses.

If you're a business owner, please share your story with them here as well as on social media (they have some great resources to help you on that front here). Everyone else, share with the business owners in your life.

How would proportional representation be implemented in a state with only one representative in Congress (like North Dakota, where I live)? Would we have to increase the number of seats in the House across all the states?

Great stuff! More on Massachusetts here: https://nathanlockwood.substack.com/p/can-the-bay-state-be-a-beacon-for