Democracy Atlas rule 1: Resist. Then adapt

Hungary teaches us how to change tactics to get ahead of shifting attacks

Rule 1: Resist. Then adapt: Under an authoritarian government, every action is designed to cement the ruling party’s governing majority. The onslaught of changes to the electoral system — and society as a whole — may come quickly and be extreme. Do not waste time developing a perfect strategy.

In the first 6–12 months, prioritize resisting election system changes pushed by the ruling faction, since they are likely to further lock in uneven dynamics for political competition. NGOs that focus on elections can be a valuable watchdog. Work with them early on so changes do not go unnoticed. Spell out the risks of significantly modifying the election system so people are sensitized and equipped to oppose the changes.

Once the rules are set, however, be prepared to work within the new system and defend it from further harmful changes. Whenever possible, put in place (strict-as-possible) limits on the room for any last-minute procedural changes designed to advantage one side over the other, and have a backup plan if you fail to constrain them. Keep resources flowing to the opposition, aim for incremental wins, and continue to register voters — ideally in a way that prevents mass challenges to eligibility.

Since returning to power in 2010, Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party have ushered in an era of precipitous democratic decline in Hungary. Like other contemporary autocrats, Orbán initially won a free and fair election but has since eroded the rule of law and reshaped the electoral system in his favor.

Over the past 15 years, Hungary’s pro-democracy forces have learned how to resist, then adapt to Orbán’s autocratic impulses — through a relentless process of trial and error.

In retrospect, that adaptation was much slower than it likely needed to be. Had pro-democracy forces recognized just how dramatically Orbán was changing the game of electoral politics — and shifted strategy accordingly — then maybe the path toward restoring democracy today would be clearer. Still, the story is not over and the Hungarian opposition has slowly learned how to adapt.

American pro-democracy leaders would be wise to take notes.

Initially, Viktor Orbán’s swift constitutional changes and legislative maneuvers caught Hungary’s pro-democracy forces flat-footed

Soon after taking power in 2010, Orbán and his two-thirds parliamentary supermajority rewrote the constitution behind closed doors and changed electoral laws to their own benefit. Within a year, the ruling party replaced the existing two-round election system for individual constituencies with a single-round to prevent smaller parties from coalescing ahead of a runoff. The government also reduced the number of electoral districts and secretly redrew constituencies to shore up Fidesz strongholds and dilute the political power of opposition-friendly areas.

Alongside sweeping constitutional changes, sudden changes to electoral laws (especially in the run-up to election day) have become a hallmark of Orbán’s rule. Every change to the electoral system is designed to bolster Orbán’s two-thirds supermajority, which is the cornerstone of his political dominance. And early on, Fidesz recognized that fracturing the opposition come election day was an effective way to preserve its power.

As New America’s Lee Drutman and Protect Democracy’s Farbod Faraji put it:

“Orbán’s Fidesz party took a more proportional voting system and made it more majoritarian.”

That shift to a more majoritarian electoral system helped Fidesz consolidate power by overrepresenting its supporters and locking out smaller opposition parties that could threaten its supermajority.

Ahead of the 2014 election, the rubber-stamp parliament passed a new law that required parties running a national list to compete in more districts in order to retain their official status, increasing the competition for opposition voters among non-Fidesz parties. The government also expedited citizenship for hundreds of thousands of ethnic Hungarians in neighboring countries, counting their votes in a secretive process overseen by Fidesz allies (and it was later revealed that over 95 percent of this bloc voted for the ruling party).

Combined with earlier rounds of gerrymandering and the uneven media ecosystem, these new laws padded the ruling party’s margins. Although Fidesz received only 45 percent of the final vote in 2014, Orbán’s electoral sleight of hand helped him clinch a two-thirds supermajority — by one seat — allowing his party to continue unilaterally passing laws and rewriting the constitution in pursuit of its illiberal agenda.

After the election, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) condemned the “undue advantage” that helped Fidesz obtain its supermajority. U.S. officials also expressed concern over the changing legal landscape favoring the ruling party.

Still, Hungary’s pro-democracy forces were caught off guard by the government’s successful manipulation of the electoral system. Although a five-party alliance tried to build support in the months before the 2014 parliamentary elections, their efforts came too late. While the alliance recognized the importance of unity and aimed to publicize how Fidesz rigged the game, its last-minute coordination fell short of creating a winning pro-democracy coalition.

The 2014 defeat forced Hungarian democrats to adapt to Orbán’s autocratic funhouse — where up is down, down is up, and Fidesz always seems to come out on top.

After eight years in the wilderness, Hungary’s pro-democracy opposition took steps to build a more unified strategy

By constantly changing the rules of the game, Orbán forced the pro-democracy opposition into a constant state of reaction. And the state-controlled media apparatus made it even easier for Fidesz to dominate the narrative at all times. But as the 2018 campaign approached, the opposition recognized that it had to adapt in order to survive. It had to work proactively, not just reactively.

At this point, a new political identity emerged: the “unified opposition voter,” representing traditional left- and right-wing voters who were turned off by Fidesz. Despite ideological differences, these voters agreed on the need to unite against the government’s authoritarianism.

Civil society groups mobilized in support of this growing constituency, and informed the public about Orbán’s continued manipulation of the electoral system. And pro-democracy voters began pressuring opposition candidates to coalesce in order to avoid splitting the anti-Fidesz vote.

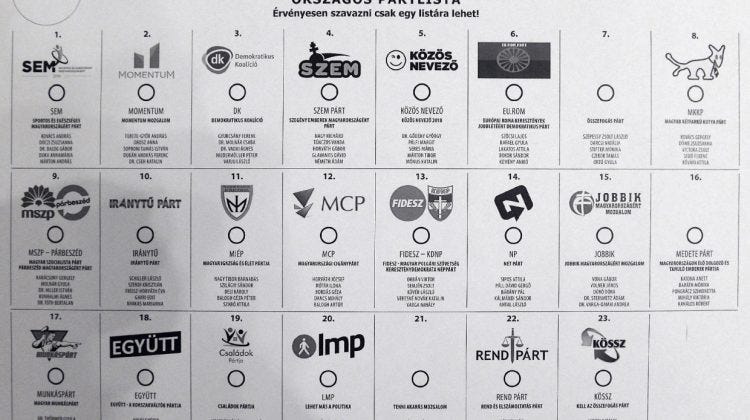

Even though Fidesz received just under 50 percent of the vote on election day, Orbán’s party still secured its two-thirds supermajority — again, by just one seat (what a coincidence, right?). Indeed, a Fidesz-backed electoral reform helped the ruling party’s margins by incentivizing the creation of “bogus parties” that siphoned votes away from the more viable opposition parties.

Beyond structural advantages, a post-election analysis of the 2018 contest by the pro-democracy group Unhack Democracy found evidence of wide-scale electoral fraud, including vote buying and intimidation. The OSCE also reported on the concerning overlap between state and campaign resources, indicating that “the ability of contestants to compete on an equal basis was significantly compromised.”

Although the pro-democracy opposition took steps to challenge Fidesz candidates one-on-one, it did not move quickly enough. And while civil society organizations urged non-viable opposition candidates to step aside for the sake of unity, in many cases, ego got in the way of effective coordination. Still, the emergence of a new opposition strategy was a sign of progress, and the lessons of trial and error would help inform future decisions by a more prepared pro-democracy coalition.

Heading into the 2019 municipal elections, opposition parties took stock of past shortcomings and agreed to form a unified pro-democracy bloc. Soon after, civil society groups organized primaries to determine which candidates would challenge Fidesz incumbents.

This time, the coordinated strategy paid off. In towns and cities across Hungary, the united opposition broke the ruling party’s decade-long hold on municipal power. The results marked a breakthrough for those hoping to restore Hungary’s democracy, especially after the opposition had lost several seats by just a handful of votes in the previous national election.

In more recent years, Hungary’s pro-democracy coalition has continued to adapt and sharpen its tools of resistance

Of course, the opposition’s gains in 2019 didn’t go unnoticed by Orbán and Fidesz lawmakers. In an effort to stall the opposition's newfound momentum, parliament passed a series of amendments to the country’s electoral laws. And once again, Fidesz increased the number of districts in which parties were required to compete — another ploy to divide opposition voters.

But those on the frontlines of Hungary’s growing pro-democracy coalition had seen this film before. Instead of getting bogged down in a lengthy deliberative process, the six leading opposition parties put aside their differences and agreed to run a joint candidate for prime minister and coordinated parliamentary candidates in the 2022 elections. After more than a decade of Fidesz rule, a pro-democracy alliance — United for Hungary — was prepared to take on the ruling party.

Building on the success of the 2019 municipal elections, civil society groups again played an important role in organizing primaries to select candidates for the pro-democracy ticket. The primary process became a major asset for the pro-democracy opposition, giving candidates the opportunity to engage directly with voters eager to challenge Fidesz at the ballot box. For the first time in over ten years, the opposition offered a positive narrative to bring disillusioned voters into the pro-democracy tent.

True to form, Orbán introduced new electoral changes in the run-up to election day. The government formally legalized “voter tourism” (already a common practice in previous contests), allowing people to register in any district regardless of their primary residence. Alongside existing laws that allowed pro-Fidesz voters in the near-abroad to vote, as well as tweaks to constituency boundaries, the new set of laws gave the ruling party additional opportunities to bolster its margins where needed. And the government’s propaganda machine worked in overdrive to convince voters that the opposition would bring Hungary into the war in Ukraine, casting Orbán as the only peacemaker in the race. Meanwhile, the pro-democracy candidate for prime minister, Péter Márki-Zay, received just five minutes of airtime in the Fidesz-controlled media during the entire campaign.

So it came as little surprise that, despite a more coordinated attempt at unity, the opposition fell short on election night. Fidesz won another resounding victory and maintained its prized supermajority, aided by its electoral contortions and the pro-democracy alliance’s muddled messaging. In the aftermath of the election, it became clear that United for Hungary was merely a marriage of convenience, unable to mount a full-throttled pro-democracy challenge to the ruling party.

Still, opposition supporters looked for lessons in their defeat. Although many had assumed that a united front of the top opposition parties was the best bet to challenge Fidesz, years of Orbán’s electoral reforms had essentially created a majoritarian system in which a singular party would be best suited to take on the entrenched incumbents.

Momentum has since shifted in that direction.

Over the past year, an unlikely figure has emerged as Orbán’s leading challenger ahead of the 2026 parliamentary elections: Péter Magyar, a former Fidesz insider who broke with the ruling party in early 2024 amid a high-profile government scandal and coverup. Though initially uninterested in joining the political arena, Magyar soon took over the Respect and Freedom Party (Tisza) and transformed it into a serious political force.

Magyar’s movement has redefined Hungarian politics, and his criticism of Orbán’s “mafia state” has resonated with voters across the country. In his first electoral success, Magyar led Tisza to a strong result in the 2024 European Parliament elections, in which Fidesz posted its worst showing on record.

Now, heading into the 2026 elections, Magyar is combining his firsthand experience dealing with Orbán’s inner circle with 15 years’ worth of lessons from the pro-democracy coalition. His clear and direct anti-corruption message has sparked a new movement and energized voters who are both exhausted by the government’s authoritarian tactics and disillusioned with the old guard opposition parties. In 2026, Tisza plans to run its own candidates in every electoral district, aiming to face off one-on-one against Fidesz across Hungary.

For the first time, a single pro-democracy party seems poised to challenge Orbán at the ballot box — the culmination of years of adaptation to the government’s ever-changing electoral manipulation. And while not everyone in the pro-democracy camp is fully behind Magyar, Tisza has led Fidesz in most public polls released this year.

Crucially, Magyar hasn’t let Orbán control the narrative. Already, he has proactively pushed back on new laws targeting his candidacy. Other recent changes to the electoral laws — eliminating districts in opposition-friendly Budapest and allowing unlimited campaign contributions — are designed to benefit Fidesz but reveal Orbán’s vulnerability against an invigorated opposition.

After 15 years of Orbán’s rule, the pro-democracy coalition is finally taking the initiative. More importantly, it has learned to adapt to a constantly shifting authoritarian environment. Victories notched along the way — like blocking the proposed internet tax that threatened free expression, organizing successful opposition primaries, and defying the government’s attempts to curtail civil liberties — have demonstrated that a strategic approach by pro-democracy forces can yield results.

Hungary’s democratic story is still unfolding.

Since 2010, it has largely been a story of trial and error, which is unavoidable when facing an autocratic government. Had pro-democracy forces recognized and responded to the authoritarian threat sooner, the path toward restoring democracy might have been made easier. But effective resistance in Orbán’s autocratic funhouse has required the pro-democracy coalition to adapt, not just react, to each new distortion thrown its way.

Since scholars of authoritarianism like Protect Democracy's experts and Prof Ruth Ben-Ghiat and Prof Timothy Snyder identify that US is now in stage of rapid authoritarian breakthrough, it is crucial that we learn from the opposition's efforts against Orban’s autocratic power grab in Hungary. Our wannabe dictator & the participants in CPAC have been Orban’s fanboys since 2022 for his creation of a Christian ethno-nationalist illiberal democracy. I'm relieved that there is now a new initiative to spread training about strategic noncooperation methods of mass defiance. www.nokings.org/rise has been in progress for a few weeks now with 1,350 trainings scheduled so far and growing.