Why are there only two candidates on the debate stage?

To add more choices, think bottom-up not top-down

On Tuesday night, Kamala Harris and Donald Trump will square off on the debate stage. It’s going to be a big night for our democracy. We’ll have more analysis of whatever comes up next week.

Before then, I want to take a step back and look at a simple question with a sort of complex answer. Why do we only ever have two candidates debating?

For as long as we’ve had general election presidential debates, there’s only been a third candidate on stage twice: John Anderson in 1980 and Ross Perot in 1992. Every other presidential debate has been a head-to-head between one Republican and one Democrat.

Yet most Americans wish they had more options for president — is that possible?

The short answer is “no.” The long answer is… “kind of yes.” The difference is in whether we think about things from the top-down or the bottom-up.

The “spoiler effect” means we’ll likely always have two main presidential candidates

The harsh reality is we can’t simply add more choices from the top-down. There’s no way to snap our fingers and add more serious presidential candidates.

To understand why, we need to first think about elections as more than just popularity contests. They’re about policy.

And policy can be understood on a spectrum. True, most political scientists encourage us to acknowledge that this stuff is multi-dimensional — views on the economy, environment, foreign policy, immigration, social issues and so on don’t always line up, well, in a line. But for simplicity here, let’s boil everything down to a single spectrum, from left to right.

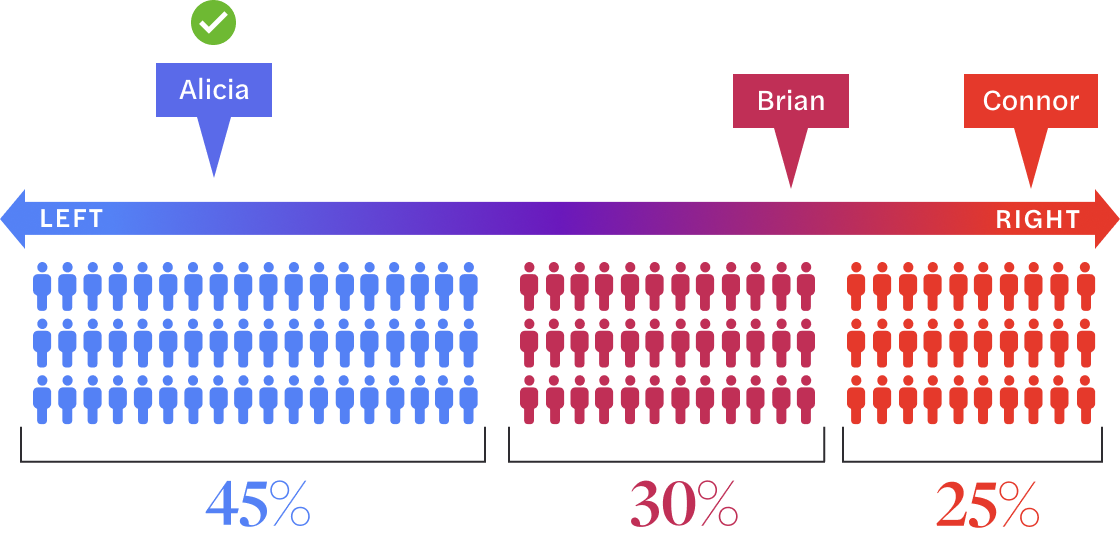

So for any election, we can plot the candidates and the election results on that line.

Let’s start by imagining an election with only two candidates. Let’s call them Alicia and Brian. Brian is a little closer to most voters’ preferences than Alicia, and in this election, 55% of the voters vote for Brian.

Brian wins. Simple. When there are only two choices, the candidate most voters would prefer typically wins.

Now let’s throw a third serious contender into the mix and see what happens.

Oops. Even though the third candidate, Connor, is closer to Brian on the issues (and a majority prefer one of the two of them), Alicia is the one who wins.

When there’s one winner, a third candidate almost universally harms the candidate they most agree with on the issues and helps the candidate they most disagree with. In other words, Connor’s decision to enter the race is all but assured to hurt the issues and priorities he cares about by electing Alicia.

This is true regardless of what Connor’s views are! Let’s say he’s actually to Brian’s right flank, not to the center. Same story. He hurts the candidate he most agrees with and helps the candidate he most disagrees with.

This is the spoiler effect.

Connor spoils the election for Brian (or vice-versa, the effect goes both ways). An additional candidate hurts the candidate that they most agree with and helps the one they most disagree with.

We can’t really avoid the spoiler effect for the presidency

This is why simply adding more choices to our party system from the top-down isn’t really a helpful option.

Now I know what you’re thinking: What about ranked-choice voting?

Generally, RCV can help reduce the spoiler effect caused by non-serious third candidates. (Explanation from FairVote here.) By allowing voters to both vote for a marginal figure no one expects to win and rank second their preferred viable candidate, the risk of spoiling goes down. This is a good thing.

But what if there’s a third serious candidate in a presidential race? What if three people are running and any of them could plausibly win in at least some states?

The problem is the Electoral College (you knew this was going to come up somehow). With the Electoral College, to be elected, you have to win a majority, 270 electoral votes. The same person has to win 20-30 different elections, simultaneously. Without a national popular vote, ranked-choice voting does little to guarantee that the electoral vote won’t still split three ways.

And if nobody gets to 270, the Constitution mandates presidential selection be thrown to the House for a contingent election. It’s not just that the House would pick, experts worry for various reasons that the process could break down into a constitutional crisis. (Thomas Jefferson called it “the most dangerous blot” in our Constitution. Mitch McConnell called it “nonsense” and supported an amendment to replace it.)

The risk of a contingent election is like a spoiler effect on steroids. A third serious candidate could not just hurt the candidate they most agree with, they could potentially blow up our democracy.

So, as long as we pick our presidents through the Electoral College, having two main presidential candidates is generally preferable to having more than two.

…But we can still create more choices in our political system

We just have to think bottom-up, not top-down.

If you look around the world, the way other countries have introduced more political choices has been to move their legislatures from a winner-take-all system (where each district produces one and only one winner) to a system called proportional representation.

Under proportional representation, multiple representatives are elected in the same district with seats allocated by vote shares.

Here’s what the change would look like in Massachusetts, which, despite being roughly ⅓ Republican, currently elects only Democratic representatives for the House (almost entirely through uncontested elections, yikes):

Under proportional representation, it’s very possible that Alicia, Brian and Connor’s parties could all win the same election, with Alicia’s party getting the most seats but Brian and Connor together having a majority. Voters are free to pick from a menu of options without the fear that — in selecting the candidate they most agree with — they’ll accidentally help elect the one they most fear. (Read more here.)

Sounds nice, doesn’t it?

But here’s where things get really cool. If we do this bottom-up, say by implementing proportional representation for the House of Representatives or for state legislatures, most experts expect the benefits of more choices to trickle upwards. All the way to presidential elections.

A proportional Congress would make presidential elections better

In a landmark paper earlier this year, political scientists Scott Mainwaring and Lee Drutman looked at presidential systems around the world and concluded that the ones with proportional representation legislatures were healthier and more stable than the ones with winner-take-all:

Whatever concerns about presidentialism exist, there is no evidence that a two-party system makes presidentialism function better. If a two-party system works well with presidentialism, it is only when that system produces nonideological, moderate parties. Whatever risks exist in combining presidentialism and multipartyism in the United States, they are far fewer than doing nothing and maintaining the divisive us-against-them status quo.

In short, the more flexible and fluid party system helps keep presidents in check, resolves conflict better, more accurately represents voters’ views, and helps sideline extremist candidates by making it easier to form cross-ideological coalitions.

For presidential elections, Scott and Lee expect — if the United States had a multi-party political system with more robust and serious third parties — that you’d likely still see two major presidential candidates, but each would represent a coalition of parties.

[D]epending on the strength of different legislative parties, we might expect slightly different preelectoral coalitions to form from election to election. As with Senate elections, we could imagine a system of fusion voting for presidential elections, in which multiple parties have ballot lines, but may support the same candidate in order to formalize their preelectoral coalition — and quantify how much support they bring to the winning coalition.

We would thus expect to see cabinets that better reflect the ideological diversity of winning coalitions, with presidents reaching out to representatives of multiple parties to govern.

In other words, yeah, we might still have two candidates debating — but each of those candidates would more consciously represent a variety of views, interests, choices, and priorities. And, through a return to fusion voting, voters could align with whichever supporting party best fits their worldview.

Here’s the really crazy thing. This is how things used to work before our current two-party system became so entrenched. Here’s the 1944 election results in New York (which is one of the few states that still uses fusion). In that election, you could vote for FDR in different ways: via the Democratic Party, the American Labor Party, or the Liberal Party.

Notice anything?

Read Scott and Lee’s whole paper: The Case for Multiparty Presidentialism in the U.S.

Read about how fusion works in practice: Fusion Voting and a Revitalized Role for Minor Parties in Presidential Elections

__

There are more layers to this particular onion, and I’d love to hear your thoughts on electoral systems, either around this question or others. Drop them in the comments.

Growing concern about pardon abuses

An important new book out this week — University of Baltimore law professor Kim Wehle on the history, law, and risks of presidential pardon abuses. My colleague Grant Tudor talked to her about the book and the threats around the pardon power. One snippet:

The most serious problem with the pardon is the lack of checks and balances to prevent abuse, a problem made worse by the Supreme Court’s decision to manufacture criminal immunity for presidents. Presidents can now commit crimes using the massive power of the office and simply pardon people who help him. Although some might call this scenario too far-fetched to worry about, the founding generation fought a revolution to get rid of an abusive monarchy and aimed to stave off another one.

Routine pardons hardly operate as a merciful safety valve for wrongful convictions and sentencing these days, either — the pardon system has been captured by the wealthy and well-connected who flood presidents for favors in the waning days of an administration. That smacks of corruption, not mercy.

It’s an enlightening conversation. Read the whole thing here.

As we’ve discussed, pardon abuses would very likely be a central flashpoint of a second Trump term. But here’s the good news: voters hate the prospect of abusive pardons. In a poll released by United to Protect Democracy & YouGov earlier this summer, overwhelming majorities of voters — including majorities of Republicans — oppose pardons for January 6 insurrectionists and other abusive pardons.

Lara Hicks and Grant Tudor explain:

The findings are unequivocal: voters are very sour on the idea of January 6 pardons. The survey also found that voters oppose self-pardons, as well as pardons for family members or staff. And it’s not just one side: the survey found that opposition to all of these potential pardons is cross-partisan.

I’m genuinely surprised that 3 in 5 Republicans don’t think a president should be able to pardon himself. Maybe things aren’t as dark as they seem.

Read more.

What else we’re tracking:

After stealing the election in July, Venezuela’s autocratic leader Nicolás Maduro has arrested his opponent (and the rightful president-elect) Edmundo González. When autocrats threaten to steal elections and jail their opponents — believe them.

According to the Justice Department, the Kremlin is engaged in an all-out effort to influence the U.S. election. This includes funding divisive online content by right-wing influencers.

An excellent summary from NPR’s Miles Parks on certification issues: “Here’s why many election experts aren’t freaking out about certification this year.”

WaPo’s Laura Meckler has a deep dive on how a second Trump term would seek to control what gets taught in history classrooms across the country. Amanda Carpenter pulls some of the wildest excerpts here.

Germany’s AfD has become the first far-right party to win a state election since 1945. Most concerning, per Anthony Faiola and Kate Brady, its growing support “has mirrored a nationwide surge in political violence and hate crimes.”

If you care about DOJ independence, you should read this from Conor Gaffney and Genevieve Nadeau in The UnPopulist: “How we can stiffen the spine of DOJ prosecutors who Donald Trump would need to prosecute his political enemies.”

Threats to election workers are disproportionately impacting women, reports Scripps. 38 percent of female elections officials have experienced threats, harassment, or abuse since 2020.

You should take the possibility of a government shutdown seriously, argues The Bulwark’s Joe Perticone.

We saw exactly what you're talking about three times in recent decades, at least regarding elections. Ross Perot's candidacy got Clinton elected twice, when the voters would have chosen the Republican in Perot's absence, and Ralph Nader got George W Bush elected, when the voters would have chosen the Democrat in his absence. Perot split the Republicans, and Nader split the Democrats, exactly as you hypothesize.

This is a great explanation of how fusion voting would enable third parties to play a meaningful, constructive role in our elections (rather than being spoilers). At the Center for Ballot Freedom, we're working hard to revive this system, which used to be common in across America until the major parties starting banning it because they didn't like the competition. Sign up for our newsletter to learn more.