The next era could come sooner than you think

This Thanksgiving, we’re thankful for the possibility of renewal

Our democracy feels impossibly stuck. The basic contours of our politics — a struggle between an autocrat relentlessly seeking to consolidate power and an opposition that can only ever seem to manage temporary victories — feel like a trap that we may never escape.

And in some ways, it’s true that we’re trapped. Although not by Trump. As a country, our politics are inevitably shaped by our two-party system. In two-party politics, elections are zero-sum games: I win, you lose. Politics becomes a tiresome, one-dimensional tug-of-war. And when the opposing team represents a very different vision of our future, the stakes of the game become existential. Our heels dig in. The rope frays.

But two-party systems are a choice. They are just one way of organizing a country’s politics, one that many political scientists warn against. It’s also, thankfully, an arrangement we can change — with a simple act of Congress (no constitutional amendment required).

The problem, of course, is the political will — and the collective belief that a different game is possible.

It’s on that measure where we feel more optimistic than ever before about the advancement of proportional representation, the single most important electoral reform that would open the door to more creative, pragmatic, proportional multipartyism. Within the last six months, several intersecting trends have begun to point towards a massive reform window opening. Not just in our lifetime, but potentially within a few election cycles.

Admittedly, many of these trends are not in themselves positive ones. (In fact, many are the convulsions of a democracy in serious crisis.) But taken together, they may also present an opportunity for democratic renewal.

Here is our case for why big electoral reform is more likely than it’s been in half a century.

Six trends that make electoral and party system reform more likely

One: The gerrymandering wars have entered a final stage of perpetual, maximum partisan warfare. Single-member districts — what supports two-partyism — are uniquely vulnerable to gerrymandering. (Unlike proportional representation, which tends to make gerrymandering prohibitively difficult, if not impossible; for more on why, read Ansley Skipper and Drew Penrose: How to end the forever redistricting wars.) You can ultimately thank our electoral system for today’s redistricting death match. Especially if the Supreme Court further undermines the Voting Rights Act in Louisiana v. Callais, we could be entering a very dark period for political representation in America as states redraw their maps every few years for maximum partisan advantage. But we can light our way out by flipping a switch and eliminating single-member districts, which make gerrymandering possible and profitable for partisan mischief.

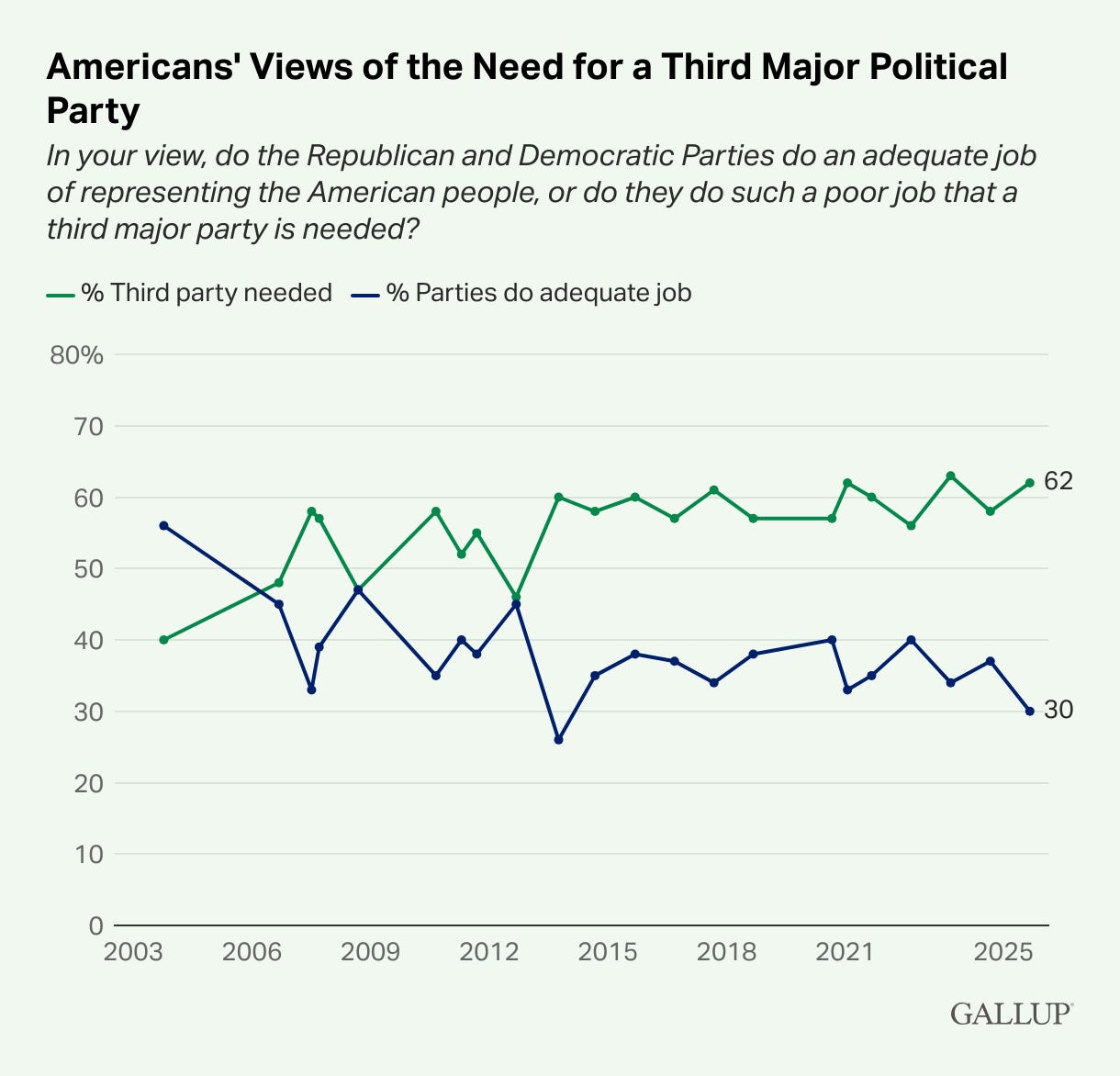

Two: Voters are desperate for alternatives. Meanwhile, as the two-party conflict escalates, dissatisfaction with our two-party system is at a historic high; a now sizable majority of Americans say they want other options. Per Gallup, only 30 percent of Americans think the existing parties do an adequate job. Beyond surveys, voters also clock their displeasure in other ways. More voters today affiliate with neither major party than at any time in the last four decades. (And more candidates see rejecting both parties as a political opportunity.) Younger voters are especially disillusioned. According to a poll by POLITICO, 64 percent of voters 18-24 believe “we need radical change.”

Three: This discontent is translating into growing support for electoral reform. According to Strength in Numbers’ October poll, 48 percent of adults say “they would support a system where states are required to assign seats in the U.S. House in proportion to the number of votes won statewide.” Nineteen percent are opposed, and 32 percent said “don’t know.” A different poll from FrameWorks Institute finds 65 percent support “changes that would make it possible to have more political parties,” including 77 percent of Democrats and 43 percent of Republicans.

Four: Serious institutions are starting to throw their weight behind reform. Earlier this month the American Academy of Arts and Sciences — one of the oldest and most prestigious independent research centers in the country — released a landmark report on how we elect members of Congress and our state legislatures. The publication is a full-throated endorsement of a switch to proportional representation:

With closely divided elections in winner-take-all systems, it is commonplace for large portions of the electorate to end up with representatives they did not vote for or support. Scholars have linked these system flaws to a broad range of negative outcomes, including escalating polarization and extremism, the underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities, and a decrease in competitive legislative races.

Given these disadvantages, Our Common Purpose calls for replacing our current system with multi-member congressional districts and a type of proportional representation.

(Disclaimer: We were both members of the working group that authored the report.)

Five: Major technological and economic disruptions seem likely ahead. In the coming years, AI could be massively disruptive to the labor market and the broader economy. It could also be harnessed to support a healthy economy and more representative democracy. Or it could be a bubble. But whether we’re in one of those scenarios or somewhere in between the three, the decade ahead is likely to be disruptive and mercurial. Our politics may continue to be strained to the breaking point. (If you think those poll numbers above are bad, just remember: These are supposed to be the good times for the American economy!)

Six: the current gravitational center of politics — devotion or opposition to Trump — maybe (just maybe) could come undone. In the past few weeks, the president’s ability to singlehandedly polarize U.S. politics around himself seems to be slipping. On the Epstein files and other issues, the divide is fraying. (As The Atlantic’s Jonathan Lemire writes: The Trump steamroller is broken.)

Incumbents are already retiring in record numbers, especially Republicans. Marjorie Taylor Greene, once among the president’s most loyal House allies, is straight-up resigning — citing her frustrations with the two-party gridlock in her announcement video. And if reporting is to be believed, this may just be the beginning of a cascade. As one anonymous House Republican told Punchbowl this week:

More explosive early resignations are coming. It’s a tinder box. Morale has never been lower. Mike Johnson will be stripped of his gavel and they will lose the majority before this term is out.

There are moments in political history when the longstanding gravitational forces collapse and new opportunities suddenly open. Donald Trump has been the central gravitational force in our two-party doom loop for a decade. That’s a long time. But the end could be in sight. And when it finally comes, it will come fast.

American politics have gone through cycles of stability, stagnancy, chaos, and rebirth

All of these factors together mirror past eras of explosive change in American history. The Gilded Age gave way to the Progressive Era. The Great Depression to the New Deal. Even Watergate gave way to far-reaching reforms.

Systems can feel dangerously trapped and unchangeable, broken and frozen — until some confluence of forces abruptly and unexpectedly arrive. Large-scale change is suddenly on the table. It’s like a machine whose gears seize up: Eventually the pressure builds until everything convulses, loosens, or breaks apart. It becomes possible to reassemble into something new.

But systems don’t change on their own. Machines don’t reconstitute themselves. (Yet.) Other democracies that have succeeded at major reform — and specifically, the transition to multipartyism — share at least one thing in common.

As our colleague, Stanford’s Didi Kuo, has argued, big reform requires “political elites to spearhead calls for change.” Those who “take up the banner of reform” and “make the case for change.” In other words, reform requires political leadership.

There are some signs of that leadership emerging — such as a bill proposed by the Blue Dog Democrats to study big electoral reform. That leadership tends to be younger, too, with officials like Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez, age 37, at the forefront. Ultimately, a new generation will enter office — maybe one less tolerant of the old ways. (Younger leaders would also benefit from reform; proportional representation brings younger people into politics.)

But the truth is, political leaders are unlikely to champion reform unless and until their constituents start demanding it. For most Americans, including most elected officials, our current system is all they’ve ever known.

They need our help envisioning a better way.

How you can help — at the Thanksgiving dinner table

You can be a part of helping speed this process along.

When you gather around the table tomorrow, *if* you talk about politics (which, you know, we don’t necessarily recommend), practice doing so outside of the entrenched divisions of our two-party doom loop. Try not to mention the name “Trump” even once. Try to find values and issues of surprising agreement, even with those who don’t normally agree with you. Or conversely, try to identify new areas of disagreement with people who tend to vote the same way, issues where, if given more options, you would actually vote differently.

Practice breaking apart the reductive two camps of polarization and pulling apart politics into something more complex and multi-dimensional.

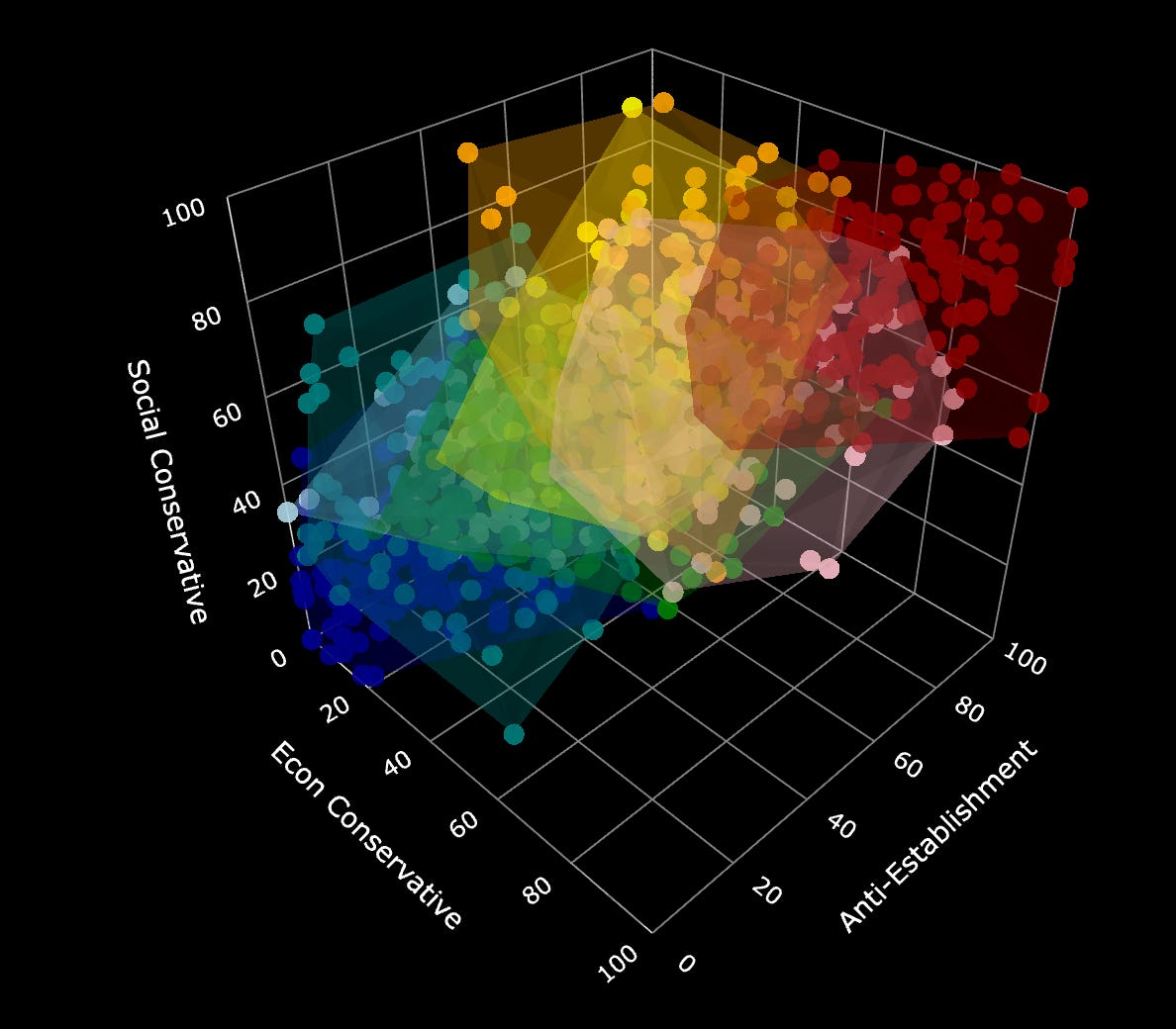

Need help thinking that way? Echelon Insights has a useful tool based on polling data to identify: which of America’s eight political tribes do you fit in?

And then, if you want to go further, start talking about how proportional representation can make this sort of multi-dimensionality — where we agree, disagree, and debate not in two camps but in multiple overlapping ones — much easier.

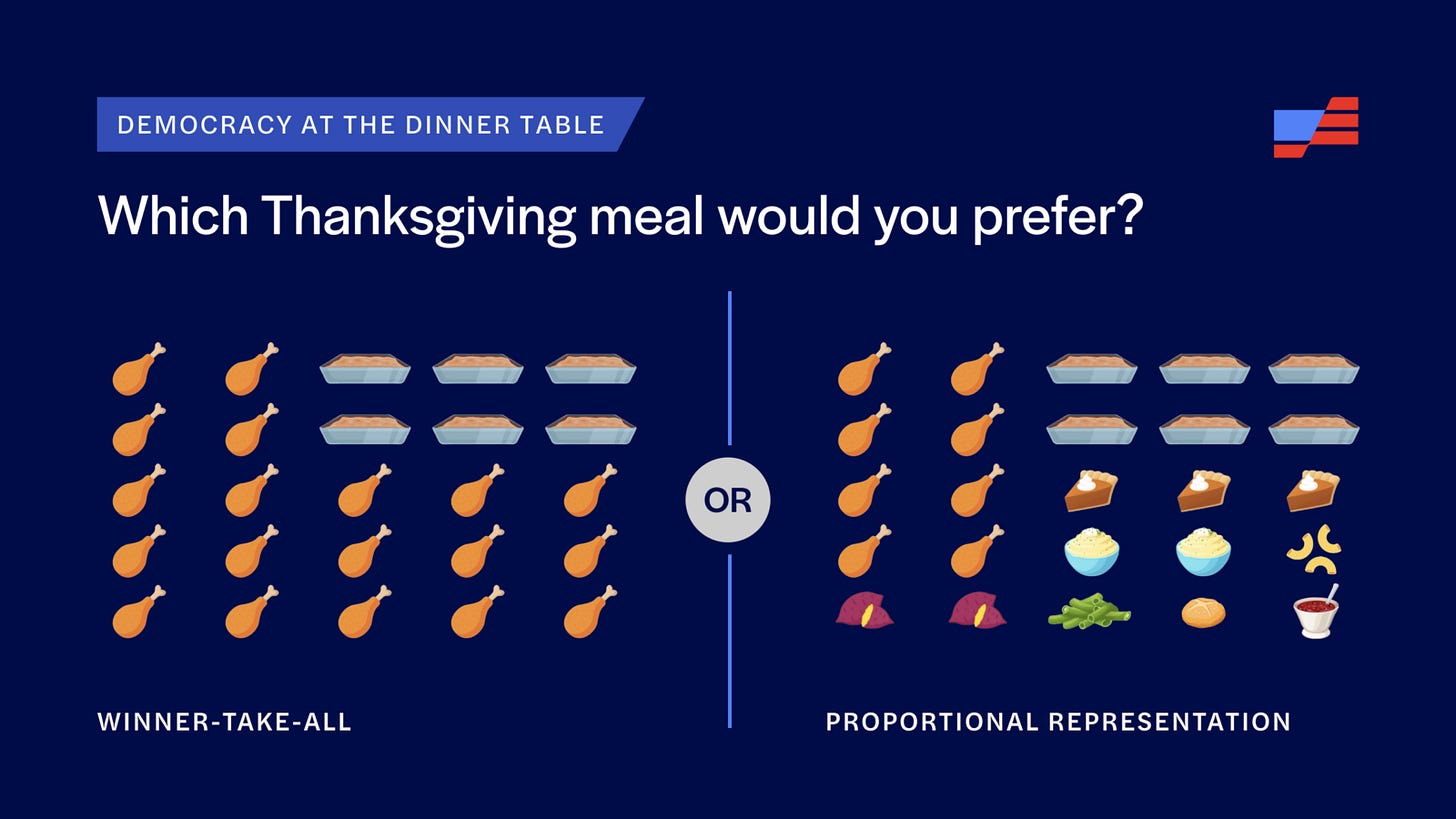

To help explain proportional representation, here’s a simple Thanksgiving analogy:

Imagine that your dinner includes everyone — all 342 million Americans — and we need to decide what to cook. We’re having trouble deciding on a menu, so we propose two different options:

Option one: We split the country up by geography and each area picks one — and only one — dish. This is how we elect Congress now; it’s “winner-take-all” because, in each district, only one dish wins.

Option two: We all vote on dishes and then divide up the menu commensurate with voters’ preferences, making sure everyone’s favorites get represented in proportion to how many people picked them. This is “proportional representation.”

In 2023, Protect Democracy and Citizen Data polled the country on its favorite dishes, using these two electoral systems. The country effectively planned two different menus: one with winner-take-all and the other with proportional representation.

Which dinner table would you rather join?

We know our answer.

Thanks for a powerfully engaging description of the possibilities of renewal! I have thought for years that the changes you propose are required to keep the USA experiment alive!

This is exactly the kind of specific structural reform conversation we need more of.

You write: “two-party systems are a choice… an arrangement we can change — with a simple act of Congress (no constitutional amendment required).” That’s the critical insight: our current dysfunction isn’t inevitable. It’s the predictable output of specific design choices made in the 18th century.

Proportional representation addresses a real architectural problem: winner-take-all single-member districts create a system where governing becomes impossible. Half the country always feels unrepresented. Policy whiplash every 4-8 years. Perpetual maximum-stakes conflict.

But here’s what makes this moment even more significant: proportional representation isn’t just a better voting method. It’s an example of thinking about governance as architecture rather than just personnel or policy. The question shifts from “how do we win?” to “how do we build systems that can actually govern effectively?”

You’re right that we’re seeing convergence: gerrymandering wars escalating to absurdity, voters desperate for alternatives, institutional support building, Trump’s gravitational pull potentially weakening. These create conditions where fundamental reform becomes possible.

The deeper opportunity is using proportional representation as a gateway to asking larger questions: What other 18th-century design choices are failing under 21st-century loads? How do we build systems that can process complexity rather than collapse under it? What would governance architecture fit for modern challenges actually look like?

Proportional representation could be the crack in the dam. Once people see that the system itself can be redesigned—that we’re not stuck with defaults from 1789—other structural reforms become thinkable too.