Last week, Congress ended the longest government shutdown in American history… with a deal that keeps the government open for about 10 weeks. In other words, we could be starting the same fight all over again as soon as late January.

If you’re starting to think that Congress is irredeemably broken, we get it.

The simple fact is that right now, Congress is a disaster. Even before the shutdown, it was not doing its job — not passing laws, not solving problems, not serving the American people. For many years, the American people have disapproved of Congress, and Congress has earned their disapproval.

Worse, Congress’ dysfunction means it has essentially abdicated its central role in our constitutional system. Congress was intended to be the voice of the American people; it is the subject of Article One of our Constitution, and the ultimate check on abuses of power by the president (or the judiciary). Congress’ inability to function is a core reason why our country has become so vulnerable to abuses of executive authority.

But is Congress hopeless? We think not.

In fact, we have an idea for how to start fixing it, and we’re pretty sure it’s one you haven’t heard before. It doesn’t require amending the Constitution, waiting for a different president, or hoping for Democrats and Republicans to have some big epiphany and start working together again.

All it requires is for the two political parties to embrace their own internal divisions — a decision which could be in their electoral self-interest.

The two-party tug-of-war

At the heart of Congress’ dysfunction lies a familiar problem: our rigid two-party system.

The American people have all kinds of different views. We are liberals, conservatives, radicals, moderates — and many independent-minded people whose views defy easy categorization.

But our system forces us to choose sides in what has become an endless tug-of-war. Nearly everything one party is for, the other party is almost instinctively against. Every “win” for one party is viewed as a “loss” by the other.

And the current rules in Congress seem designed to escalate this two-party conflict.

In our modern-day Congress, party leaders have tight control over the legislative agenda, and they use that control to block bills that would divide their own members. In practice, this means that if half of the majority party opposes a bill — even a bill that would be widely supported by the rest of Congress — that bill doesn’t have a chance of even making it to a vote. On any given issue, the most extreme half of the ruling party can effectively block progress.

And that’s a major reason why we’ve experienced increasing conflict and gridlock.

Both parties have taken turns winning narrow control of Congress. But the insistence on party unity makes them beholden to their extremes and makes it extremely difficult for Congress to act. This kicks off a cycle:

Extreme-driven gridlock makes the opposition party even more frustrated, heightening the conflict and polarizing them toward the opposite extreme;

Growing polarization between the two parties narrows the margins of victory and makes gridlock even worse; and…

The cycle continues, as worse gridlock causes more polarization and greater conflict.

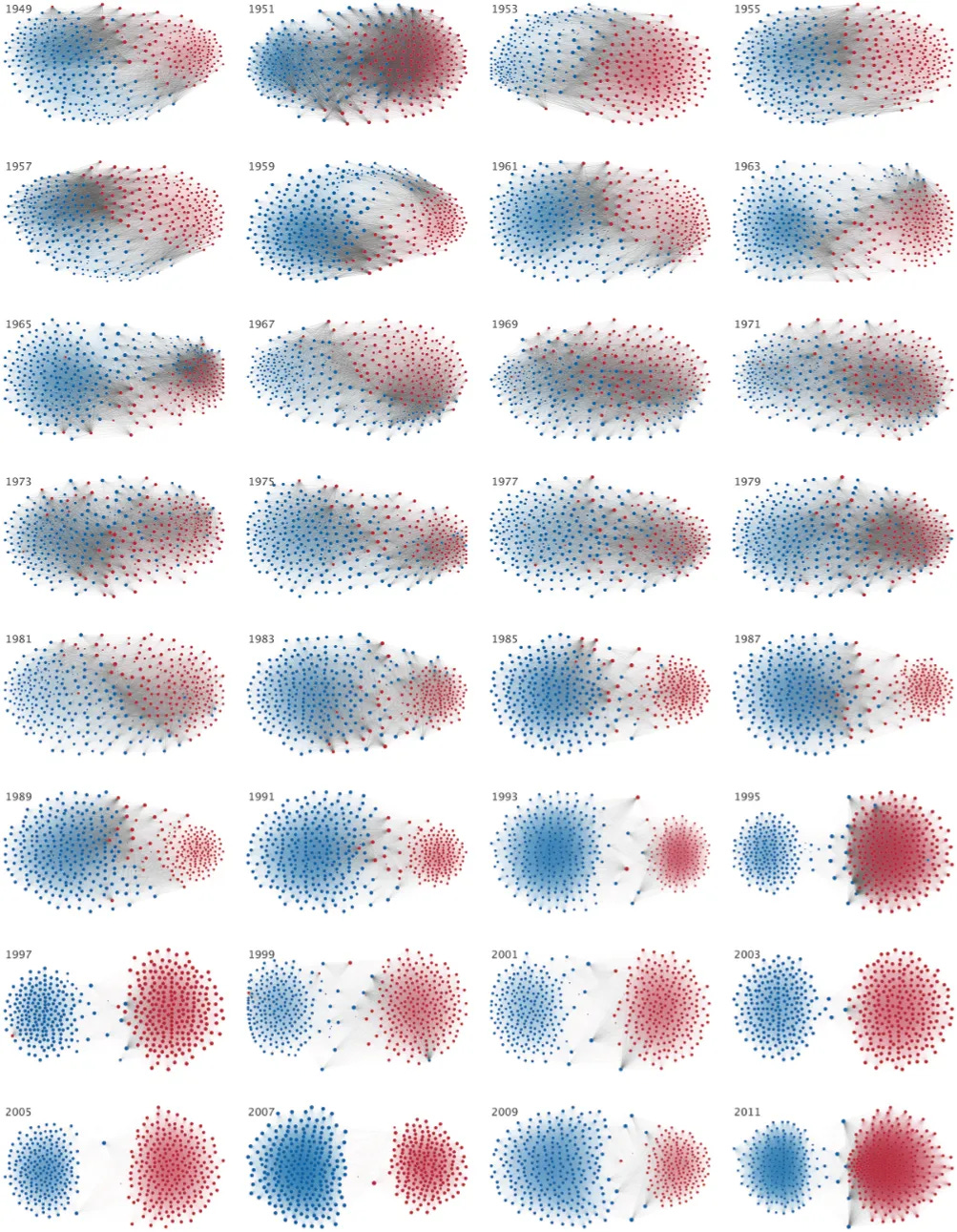

If you plot legislators’ voting patterns over time, as researchers have done, you can literally see this polarization cycle in action.

Eventually, this cycle risks tearing the country apart.

Unless we do something about it.

Read our full report: Democratize Congress.

The sub-party solution

How do we break through two-party gridlock without upending our entire system? By empowering the different groups within the existing parties.

The basic idea is this: In a system with only two rival groups, there’s very little reason for those groups to cooperate. But what if you informally divide those two into, say, four or six sub-groups? And you then give each of those groups some freedom to try to build a coalition around their ideas by negotiating with one another?

In short, if party leadership were to give up some measure of gatekeeping authority, they could diffuse two-party conflict, and free Congress to legislate through more complex and dynamic coalitions.

In this new arrangement, all the factions within Congress would have an opportunity to pass legislation. They may even feel some competitive pressure. It’s not as appealing to just keep yelling at your opponents if your peers are finding ways to work with them and get results.

We like to think about these smaller groups as “sub-parties.” There are already some distinct sub-party-esque groups in Congress, particularly in the House of Representatives, which contains Progressive Democrats, Freedom Caucus Republicans, Blue Dog Democrats, the Republican Governance Group, and others.

But these groups aren’t very visible to the American people, and more importantly, they don’t have any real opportunities to get things done. Almost anything they want to accomplish has to be channeled through party leadership — which usually means that it either gets sucked into the two-party vortex, or it ends with a divisive, party-line vote.

The Progressives may want to work with the Freedom Caucus to ban congressional stock trading; the center-right may be willing to work with the center-left on tariffs and trade or immigration. But there’s little point even trying when these proposals may never get a vote.

What we need is to change the rules to empower sub-parties and give them opportunities to access the legislative agenda. That will require creative changes to the current congressional rules. But if more members are given the chance to show genuine leadership, invest in new ideas, craft new coalitions, and put their proposals before Congress, members may gradually see less value in partisan warfare and more value in trying to get things done.

A democratized Congress could restore the popularity and effectiveness of our political parties

Right now, voters dislike both parties, and that unpopularity drags down their own candidates. Candidates often try to say “I’m a different kind of Democrat [or Republican],” but in a heavily national media environment, voters have difficulty distinguishing one kind of Democrat or Republican from another. There may well be districts that would elect a Republican who prioritizes healthcare or a Democrat who is pro-life or a candidate who is more to the left or the right of the one they’ve elected. But electing such unusual candidates has become a rare occurrence because the thing that speaks the loudest is the “D” or the “R” next to the person’s name.

Real, meaningful sub-parties could help voters understand the diversity of views in Congress. And that would allow the major parties to have their cake and eat it too. Their left and right-wing members could be unabashedly left and right-wing, their moderate members could be unabashedly moderate, and all without one side skewing the voters’ perception of the other.

A party that embraces its own divisions could win elections with an actual big tent coalition that better represents the American people.

The big question of course is whether party leadership will be willing to do that — willing to embrace the uncertainty of change, which often has winners and losers. But they should be asking themselves, “what exactly do we have to lose?”

No one likes the current system. The voters hate it. Members of Congress are leaving in record numbers. The leaders of the two parties themselves are constantly fighting an endless, thankless fight. Even when they win, the prize they receive is a job that is both temporary and extraordinarily difficult: herding cats so that an unpopular party can attempt to lead an even-more-unpopular institution.

Ironically, giving up a measure of authority could make it much more possible for them to leave a legacy of accomplishment.

And the beauty of the sub-party solution is that it faces fewer procedural hurdles than most other actions a congressional leader can take. It doesn’t require the president’s signature. It doesn’t need the approval of the Supreme Court. It doesn’t even require the House and the Senate to agree.

All it requires is for leaders in each chamber (or either) to be willing to make changes to their own rules — to recognize that the status quo isn’t working, and to have the courage to find a new way forward.

Learn more about the path to a more functional Congress.

This is excellent structural analysis. You've identified the core design flaw: a two-party system where the most extreme half of either party can veto everything, creating a tug-of-war that nobody wins.

What makes this proposal so compelling is that it doesn't require constitutional amendments, court rulings, or hoping politicians become better people. It just requires recognizing that the current incentive structure isn't working - and that party leadership has the authority to change it themselves.

More of this kind of systems-level thinking, please.

Both parties, when in the majority, follow a version of the Hastert Rule (a bill only makes it to the floor if supported by a majority of the majority), which guarantees that many bills which might be supported by a majority of representatives are never considered. Eliminating that rule would be a step in the direction you suggest. But, as you say, that requires a willingness by entrenched leaders to relinquish control.