How Congress can get us off the tariff roller coaster — forever

Plus, a fully armed and weaponized pardon power

Over the course of less than a day yesterday, the effective average tariff rate on imports to the U.S. dropped by about 10 percent before immediately shooting back up.

In real terms, that means taxes on Americans were cut by about $400 billion, roughly the GDP of South Africa … for about 20 hours.

This time the swings weren’t because of erratic White House decisions. Instead, the little-known Court of International Trade (which is still, to be clear, a U.S. court, not an international one) ruled against many of Trump’s tariffs — only to have the ruling quickly stayed on appeal.

This is the latest chaotic turn in the tariff saga, which has swung wildly for months. This uncertainty is — to put it bluntly — an insane, almost nausea-inducing way to set massive economic policies. Tariffs impact basically every person in the country, if not the world.

There’s ample room to debate what role (if any) tariffs should have in our economic policy. But there is a better way to do this. The president’s party controls both houses of Congress. In a normal, healthy democracy, trade policy would be set rationally, deliberately, and predictably. The executive would lead negotiations with the world and Congress would have the final say in either codifying deals or erecting unilateral trade barriers. That’s how it used to work — and how the Constitution expressly suggests it should work — but no longer.

Nowadays, this insanity is our reality. This chaos is almost certainly how things will continue to go for the rest of this administration, if not beyond. The crux of this current legal dispute — and really, so much of Trump’s tariff roller coaster — comes down to a specific bug in the system: presidential emergency powers.

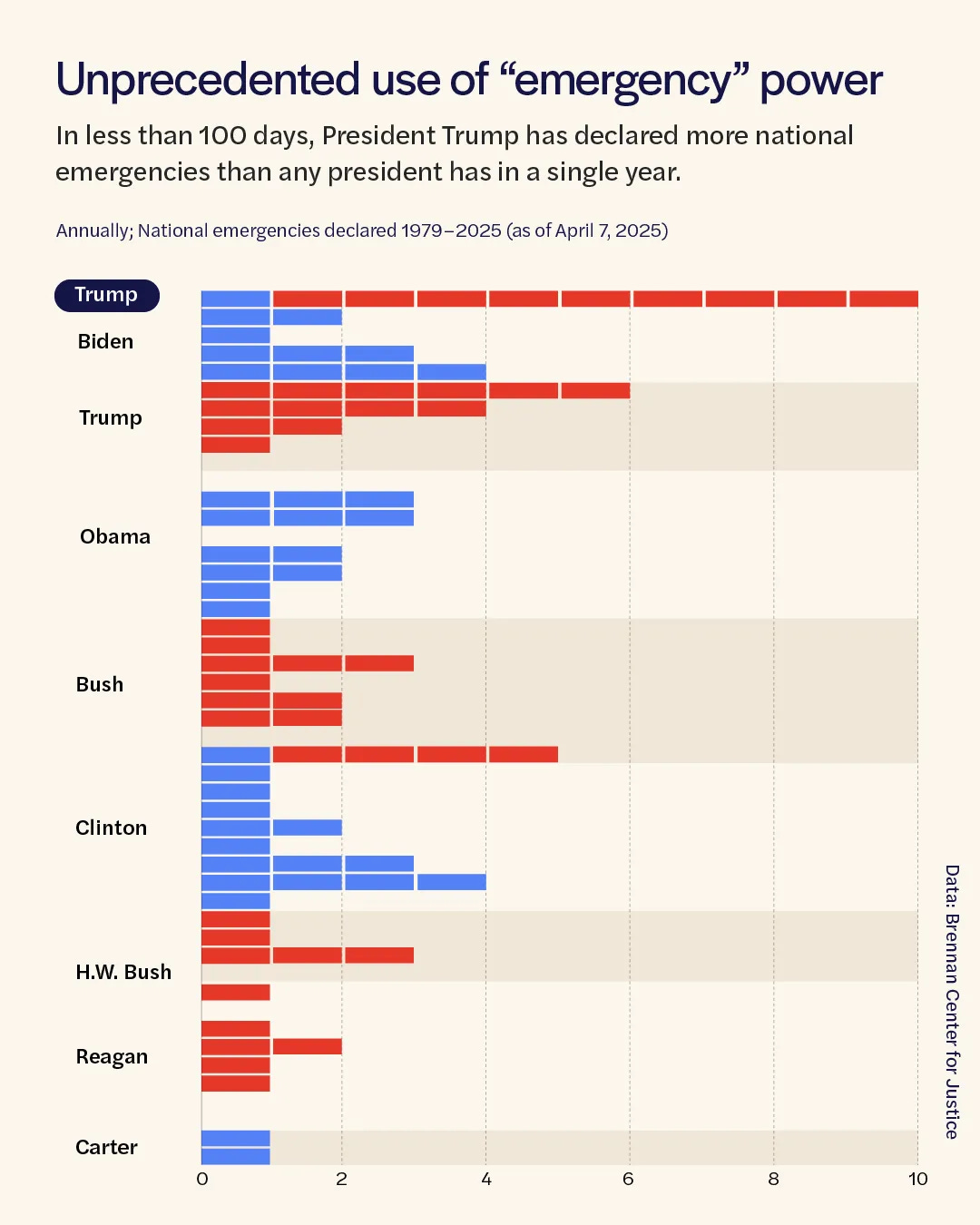

Before now, no administration sought to abuse legislatively granted emergency powers to such a brazen degree. But the possibility of abuse was arguably always there (just as it was in other areas, like the pardon power, on which more below). Now that Trump has turned what was intended as a tool of last resort into a first-strike weapon for tariffs (and also so much more, also see below), there’s no going back.

Until we reform the president’s ability to implement wild and erratic policies under the guise of an “emergency” — this roller coaster does not stop. Buckle up.

How do presidential emergency powers connect to tariffs?

As I wrote in April, the central question in Trump’s tariffs revolves around a law that (arguably accidentally) allows the president broad unilateral powers if he has declared a national emergency:

The short answer to a long and legally complicated question is that Congress, in the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), delegated powers to the president to “regulate… importation” when he has declared a national emergency.

Emergency powers are meant to give the president flexible authority to act quickly, but only in actual emergencies, sudden events that require an immediate response. The U.S. has had a trade deficit since the 1970s. While it’s gone up and down, and there are heated debates over whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing, it’s hardly an “emergency” (here’s how The Economist summed up the pre-tariff American economy). But President Trump declared it to be one in order to claim unfettered control over tariffs.

If you’re interested in the legal details of how the court’s ruling connects to the IEEPA, the Brennan Center’s Liza Goitein has a helpful explainer thread:

At the same time, the danger of abuse of emergency powers goes way beyond tariffs. A significant portion of Trump’s policy agenda has attempted to skirt Congress by way of these powers. Everything from fossil fuel regulations to mineral extraction rules to militarizing federal lands at the southern border has been predicated on dubious emergency declarations. And there may be more around the corner.

In the first 100 days alone, Trump declared more emergencies than any president before him did in a year.

The problem: “Emergencies” are often subjective

I don’t know how the appeals courts (or, if it gets there, the Supreme Court) will rule on the tariff cases. No one does.

I suspect most Americans would see these abuses as clearly illegal — an emergency can’t just be whatever the president says is one, right? And last however long he wants? And unlock any number of powers no matter how attenuated the connection to facts on the ground?

But courts have a very inconsistent track record in policing emergency powers. In 2020, the Supreme Court refused to block the first Trump administration’s efforts to skirt Congress on border wall funding with emergency powers (a case in which Protect Democracy secured an initial injunction). But then in 2023, the same justices struck down President Biden’s attempt to forgive student loan debt under a pandemic emergency declaration.

However you read the courts’ past rulings on emergency powers, I think it’s clear that we’re unlikely to get a predictable legal standard anytime soon. Part of the problem is that, even in a good faith context, there’s a lot of room for subjectivity around what counts as an emergency and what powers that unlocks. And so there’s always going to be ambiguity over exactly when, why, and how far the president can push emergency powers.

Let’s say we didn’t have a president known for changing his mind. The unpredictable tug-of-war between the White House and the judiciary still makes some uncertainty inevitable.

In other words, even if TACO didn’t stand for “Trump Always Chickens Out,” it would still stand for “Tariffs Await Court Opinions.”

The solution: We push decisionmaking back towards congress

It does not have to be this way.

There is nothing in the Constitution (or the IEEPA) that says the president must be granted broad and unilateral emergency powers that can only be checked if the courts happen to decide to do so on whatever timeline they follow.

We still have a third branch of government, known as “Congress,” one that is supposed to make authoritative and lasting policy decisions through something we call “laws.” To get off the roller coaster, all Congress has to do is re-assert its lawmaking authority — taking back some of the power that it has delegated to the president.

On tariffs, this could be as simple as the bipartisan Trade Review Act of 2025, which:

Requires the president to notify Congress of new tariffs,

Requires the president to provide a justification for new tariffs to Congress and,

Sunsets new tariffs after 60 days if they are not approved by Congress through a joint resolution.

This law was supported by a wide range of Republican senators: Mitch McConnell, Susan Collins, Chuck Grassley, Jerry Moran, Lisa Murkowski, Thom Tillis, and Todd Young.

Or, more broadly on emergency powers, there have been proposed bipartisan reforms like the ARTICLE ONE Act that give Congress a similar review and oversight role in all emergencies. In short, these would codify that “A president’s declaration of national emergency may stay in place for up to 30 days. At that point, the emergency would automatically terminate unless a majority of both the House of Representatives and the Senate have approved it.”

That way, emergencies are reserved for true unexpected emergency situations — not for making major long-term policy decisions that entirely evade the first branch.

Again, no one knows what’s going to happen with the lawsuits over Trump’s tariffs. But I am willing to bet that 30 days from now we will still be on the roller coaster.

The pardon power has been fully weaponized

Speaking of powers that have been extended beyond the breaking point… This week, the president issued a series of pardons to political supporters, seeking to, as the Times put it, “burn the ledger.” According to the Washington Post’s Philip Bump, he has now wiped away more than 700 years of prison time for his allies (gift link).

Ed Martin, the president’s new pardon advisor (who was forced to withdraw as Trump’s nominee for U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia because of his ties to January 6th rioters) was explicit about things, tweeting:

In one case, Trump pardoned Paul Walczak, a former nursing home executive convicted of tax crimes. Per The New York Times, the appearance of corruption is fairly remarkable:

The [pardon] application focused not solely on Mr. Walczak’s offenses but also on the political activity of his mother, Elizabeth Fago.

Ms. Fago had raised millions of dollars for Mr. Trump’s campaigns and those of other Republicans, the application said. It also highlighted her connections to an effort to sabotage Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s 2020 campaign by publicizing the addiction diary of his daughter Ashley Biden — an episode that drew law enforcement scrutiny. …

Still, weeks went by and no pardon was forthcoming, even as Mr. Trump issued clemency grants to hundreds of other allies.

Then, Ms. Fago was invited to a $1-million-per-person fund-raising dinner last month that promised face-to-face access to Mr. Trump at his private Mar-a-Lago club in Palm Beach, Fla.

Less than three weeks after she attended the dinner, Mr. Trump signed a full and unconditional pardon.

The president is reportedly even considering pardoning the extremists who attempted to violently kidnap Gretchen Whitmer, the Democratic governor of Michigan. If Trump does so, this will be another explicit licensing of political violence to advance his political fortunes, following the massively unpopular pardons of January 6th insurrectionists.

It can be tempting to treat these abuses as the new normal — that the president’s sweeping pardon powers are now free to be weaponized and abused to whatever degree. It’s true that the chances are slim that weaponized pardons will be significantly curtailed in the near future. But that does not make any of this constitutional (or appropriate or just).

Last year, my colleagues Grant Tudor and Justin Florence wrote a massive report on how and when presidential pardons violate core constitutional provisions and principles. There are four types of abusive pardons:

We’re seeing all four of them these days.

And, someday, the time will come when we again have the opportunity to curb and check the pardon power. Read about the options for doing so here: Checking the Pardon Power: Preventing & Responding to Abuse

What else we’re tracking:

If you haven’t watched Ian Bassin’s commencement address at Wesleyan from last weekend, I highly recommend it. It’s the boost you need going into the weekend.

The reconciliation bill includes a provision that attempts to hamstring courts’ ability to enforce judicial orders. Berkeley Law Dean and constitutional law icon Erwin Chemerinsky explains in Just Security why this is: A terrible idea.

Our electoral system dilutes Black political power, argues Protect Democracy’s Deborah Apau for the The Houston Institute for Race & Justice. It doesn’t have to be this way.

“Trump's plan to deploy the military for immigration enforcement will set a dangerous precedent that'll undermine our democracy,” writes Christopher Purdy in The UnPopulist.

Big scoop in Semafor: The California State Senate is probing whether CBS’s parent company might violate state laws against bribery and unfair competition in its proposed settlement with Donald Trump. Executives would also do well to keep in mind: Regardless of what this administration chooses to enforce, the statute of limitations on federal bribery law is generally five years.

This piece by M. Gessen will not make you feel good, but you should read it anyway. There is a “moment when the shock fades and the (figurative) show goes on. I think we are entering that moment in the United States.” Beware: We are entering a new phase of the Trump era.

What you can do to help:

Do you run or work at a nonprofit of any kind? If you don’t, I am certain you know at least some people who do.

Help them prepare for worst-case scenarios by sending them this list: 22 things to do if you’re targeted by the White House.

Preparing for potential politicized attacks (from our country’s democratically elected leadership, no less) is never pleasant — all of us would like to reassure ourselves that someone else will be the next target. But hope for the best, prepare for the worst.

As usual, a lot of good information. The Trade Review Act of 2025 will need broad support to overcome a Presidential veto. Not likely, but it could happen as the economy gets worse and worse.

Can we get The workers and would they rather make weapons for the "No Tolerance Hacking and Market scandal" Than The Lively Party scene.