A practical path to ending the two-party system

Why allowing multiple nominations is the first step to multiple parties

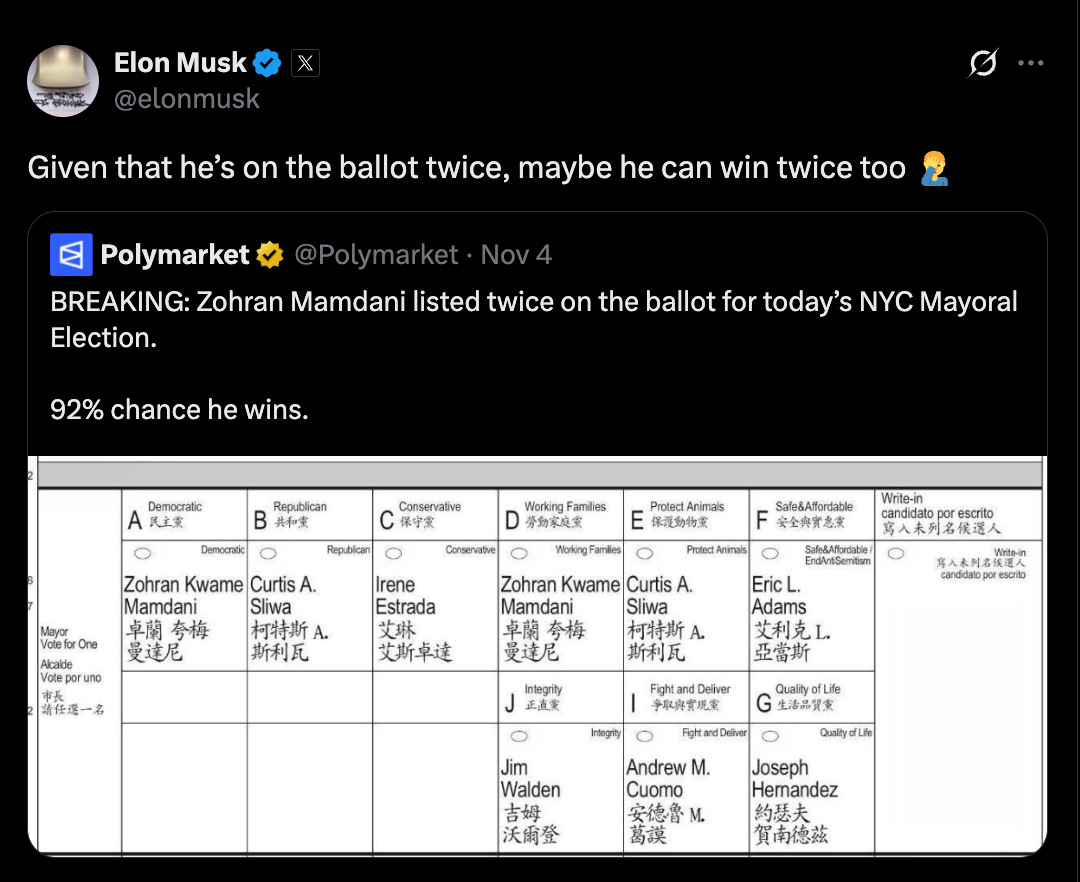

On Nov. 4, the richest man on earth inadvertently drew his followers’ attention to a little-known piece of American electoral heritage.

No, this wasn’t a ballot error. New York is one of the few places in the country that still gives multiple political parties the freedom to nominate the same candidate — a longstanding system known as fusion voting. (In this case, Democrat Zohran Mamdani and Republican Curtis Sliwa were each nominated by two different parties.)

It isn’t surprising that this system was unfamiliar to Musk — most Americans have never encountered it — but it is a little ironic. In the not-so-distant past, he tried to build a third party, the “America Party,” only to realize just how difficult it would be to mount a nationwide challenge to the two major parties in the United States. Even his riches aren’t enough to overcome the structural obstacles that keep us stuck in a two-party doom loop.

Despite those obstacles, many political scientists believe having more than two viable parties would be healthy for American democracy — and fusion voting may be the key to getting there.

While it may seem unfamiliar to those of us who don’t vote in New York or Connecticut, the truth is — fusion was commonplace across the country for much of our history. And returning to it now could forge a path to a more representative and effective democracy.

Fusion voting shaped American democracy

Up until a century ago, fusion was common practice in elections throughout the U.S. When large groups of voters found themselves boxed out by the two-party system, fusion was the way that they mobilized to push for political change.

Prior to the Civil War, anti-slavery activists struggled to have real electoral or legislative impact in an era when both the Whig and Democratic parties resisted challenges to slavery. That was until they came together in the Free Soil Party, running their own candidates where they could win outright and cross-nominating candidates from the two major parties who were willing to take a stand on the issue.

A generation later, farmers and workers found themselves similarly marginalized by the lopsided and corrupt politics of the Gilded Age. They launched a new Populist Party (often called the People’s Party) that fused with Republicans in the South and with Democrats in the Midwest and West. They proved so successful that in some cases the major party in a state became the fusion user and simply adopted the Populist slate of candidates wholesale. The Populist movement pushed for reforms to election, education, and labor policies, just to name a few.

Unsurprisingly, the two major parties did not especially like the extra competition. In state after state, legislatures banned the practice of fusion.1

The problem is the two-party system

By banning fusion voting, the two major parties entrenched themselves in power — to the detriment of our democracy.

A recent Quinnipiac poll found that 53 percent of Americans do not think democracy is working, and 79 percent believe the country is facing a political crisis.

Americans say they are unhappy with the current system — especially our two major parties. 38 percent of American voters don’t think either party fights for people like them, and only about 20 percent of people who identify as Republicans or Democrats think their own party has “a lot of good ideas.”

The two-party system, combined with our winner-take-all system (in which the party or candidate that wins a plurality of votes wins total representation of the jurisdiction) and increased geographic sorting, has resulted in uncompetitive elections that offer only bad options for voters.

For too many voters, too much of the time, their options on the ballot are either a heavily favored candidate from one major party, a long-shot challenger from the other major party, and maybe — maybe — an option to waste their vote on a third-party candidate. In plenty of cases in local and state races especially, only one candidate from the locally-dominant party even bothers to run.

And voter dissatisfaction isn’t the only negative consequence for our democracy. The two-party, winner-take-all system disadvantages minority voices, stifles competition, exacerbates polarization, and escalates extremism.

Read more: How our electoral system shapes our politics.

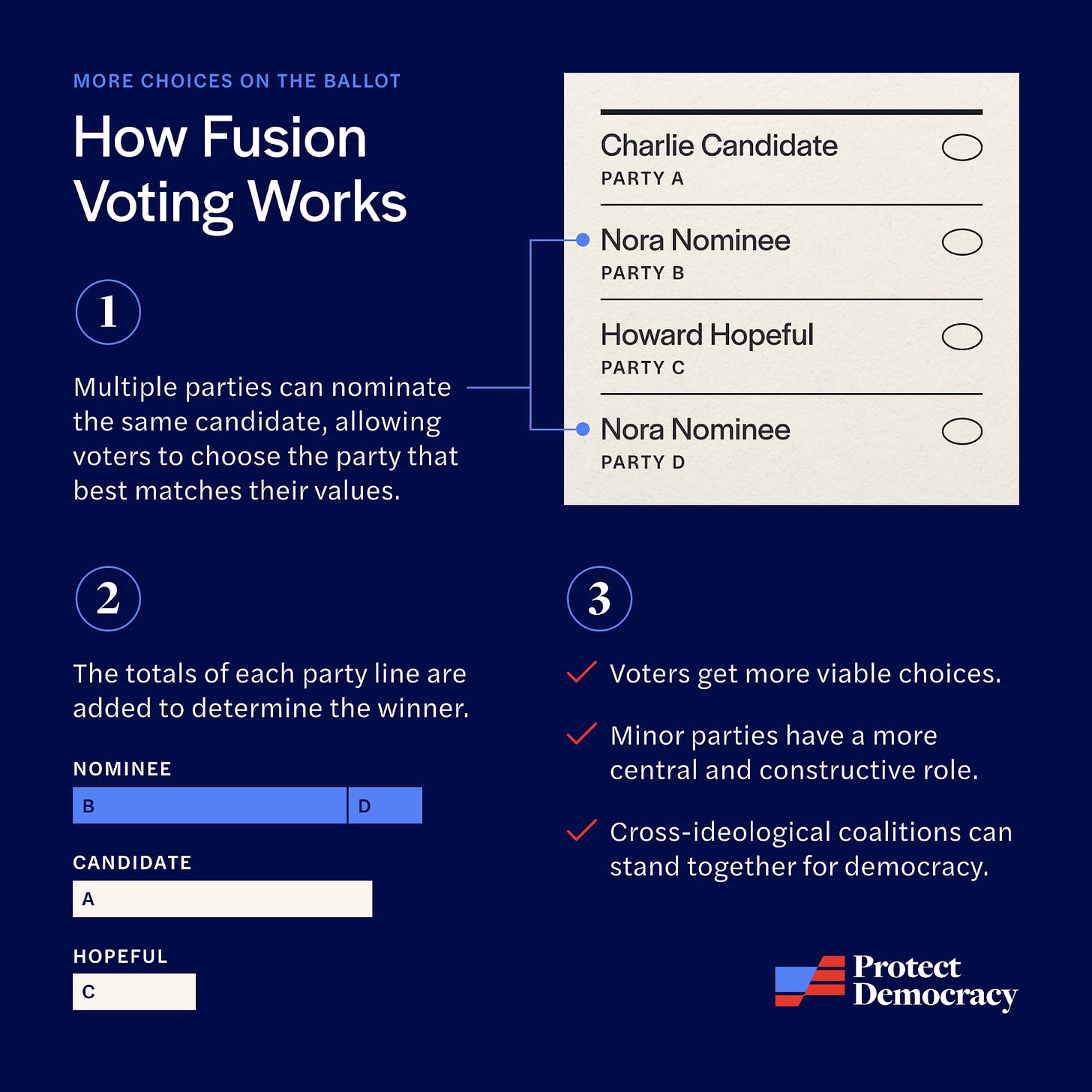

Why fusion voting

Again, fusion is the system of allowing more than one party to nominate the same candidate, and those nominations all appear on the ballot. With fusion, voters can choose the candidate they prefer, but do so on the ballot line of the party that best matches their political views and values.

Fusion voting, in short, lets the voter vote for two things at once:

The candidate they find most acceptable (or least unacceptable) to represent them.

The party that most reflects their values and priorities.

Because the votes on each line are counted separately before being added together for a candidate’s total votes, elected officials know exactly how much of their support came from each party, giving minor parties real heft during policymaking and giving voters a way to demand more responsiveness from their representatives.

The impact that fusion voting could have on cracking open our party system is not theoretical — it’s part of American political history.

Read more: Fusion voting, explained.

Today, there is growing recognition that re-legalizing fusion voting would help to address some of the dysfunctions in our current politics. It would empower a wider range of voices to meaningfully participate in politics, create a pathway for moderates to help balance our party system against extremism, and provide a pathway back to engagement for Americans who feel disillusioned with our democracy.

Compounding benefits for democracy

Fusion voting is a relatively modest change to our electoral system that would create opportunities for a more representative and effective democracy. But its benefits could be even wider — opening up pathways to other significant reforms.

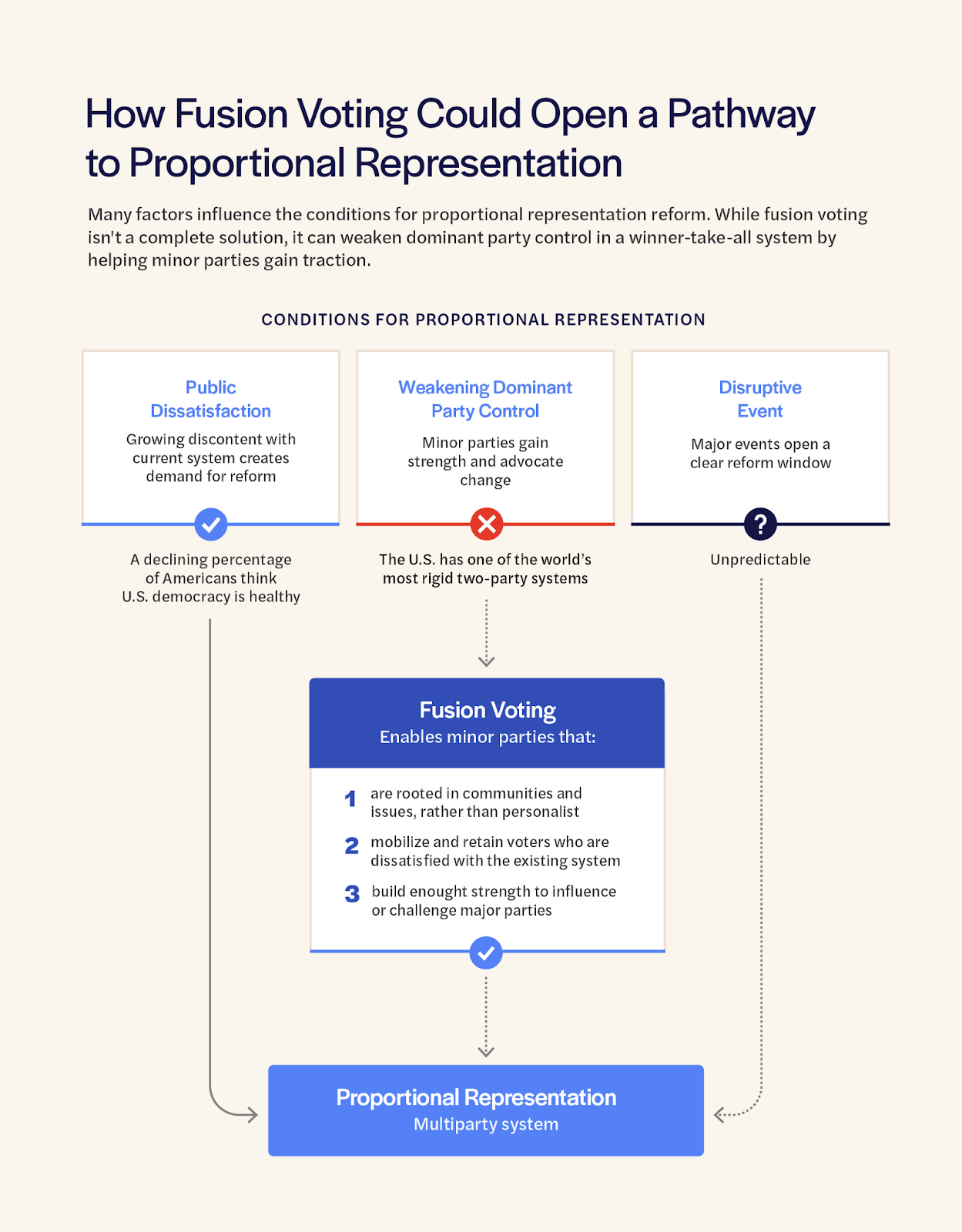

Experts have long pointed to adopting proportional representation as one of the most powerful changes that Americans could make to our democratic institutions. Proportional representation would make the government more representative of and responsive to its citizens and make it harder for authoritarians to co-opt the political system.

Read more: Proportional representation, explained.

While many Americans are open to the idea of proportional representation once they know what it is, the path towards reform isn’t always obvious.

That’s where fusion voting comes back into play.

When we look at other countries that have adopted proportional representation, there are many paths forward but a few prerequisites come up again and again — like widespread dissatisfaction with the current system or big disruptions that create clear reform windows. One common factor is a a break in the major parties’ hold over the political landscape — episodes in which minor parties or new political movements start to gain support. When the parties that dominate politics expect that they will continue to do so, they have no reason to embrace (or at least acquiesce to) calls for reform. They’re doing just fine with the current system, thank you very much. But when that changes, reform becomes more likely.

In the U.S. today, a major potential obstacle to large-scale reforms like proportional representation is just how entrenched the two-party system has become.

Americans are unhappy with the system, but that has not automatically translated into room for more voices. (Again, if even the world’s richest man can’t get a new party off the ground, the barriers must be pretty darn high.)

Fusion encourages the growth of new parties that can channel widespread dissatisfaction with our politics into a sustained demand for proportional representation. There are three main reasons why the types of parties that emerge through fusion voting could help move us towards proportional representation:

First, fusion advantages parties that are rooted in existing networks and communities. Unlike so many “outsider” third-party efforts in recent memory, fusion does not lend itself to organizing around celebrity candidates or one-off elections. Because the currency of fusion is votes and fusion parties need to distinguish themselves from the major parties in order to maximize support, they tend to grow out of or build on existing organizations or movements. The Free Soil Party built on the infrastructure of the abolitionist movement. The Populists grew out of the Farmers’ Alliances and the Knights of Labor. Fusion parties are typically not hollow in the ways that major parties today are. They have organizations and preexisting engaged constituencies — not just brands or negatively polarized political tribes.

Second, fusion parties have strong incentives to be responsive to voters and advance their supporters’ priority issues. Fusion parties have to reliably demonstrate that their nomination is valuable at election time, or candidates will not engage with them. That value comes from parties’ ability to build loyalty among their voters. That requires not just the ability to turn them out (see above about having actual organizational capacity) but the ability to deliver on policy promises. If voters don’t think fusion parties can be effective in influencing legislation, they won’t bother to vote on their ballot line.

Both historically and recently, fusion parties have had notable success in pushing major parties to advance their policy priorities — from the Conservative Party’s backing of fiscal policies in New York to the Working Families Party’s push for paid sick leave in Connecticut. Fusion parties do not just pop up at elections to help major parties and then disappear until the next cycle — they push for policy and legislative change.

Finally, fusion parties have proven to be remarkably strategically flexible. While fusing their support behind major party candidates is the main way these parties participate in elections, it is not their only move. Many fusion parties have built enough power to run their own candidates in at least some races — the Free Soilers and Populists did this a century ago, as have, occasionally, the Conservative and Working Families parties in recent years.

Americans are increasingly looking for ways to make democracy more representative, responsive, and resistant to authoritarianism. Re-legalizing fusion voting in more states would create room for more voices and help channel those desires into change.

Learn more about how fusion voting can lead to proportional representation.

Today, only New York and Connecticut allow fusion voting.

Frankly, I prefer the Alaska plan … open primary where the top 5 candidates go to the final election, and preferential choice ar that time.

Fusion voting may help as an interim measure, but I am sceptical of it as a long term fix.

New Zealand (where I am writing from) has had Mixed Member Proportional Representation since 1996 and our multi-party parliament is now a squabbling shambles. This has occurred because minor parties negotiate “deals” with the major party after an election to enable the major party to govern. Unpopular minor party policies are supported the major party in return for the minor parties agreeing to support the major party’s policies. This results in deeply unpopular decisions being rammed through our parliament.

In my view, democracy is in decline worldwide - regardless of the electoral system used - and I think is occurring primarily because:

1. Political parties are inherently competitive – not cooperative.

2. Election cycles result in wasteful short-term decision making

3. Government decisions are made with insufficient consensus.

While the following suggestions were written for a tiny New Zealand audience, (which has a small number of electorates, 3 year terms and a single layer house of elected representatives), I think democracy’s deficiencies could be fixed relatively quickly; with possible solutions being:

a) Encourage independent political candidates and enfeeble political parties by limiting donations to parties to a small amount, say $50/year maximum from any one individual or organization

b) Implement elections that “roll” around the country every month by dividing the country into 72 electorates, with 2 geographically disparate electorates voting on a rotating basis every month of the year. In its designated month, every electorate would elect one individual by popular vote to serve that electorate for a 3 year term.

c) To reduce the impact of political parties, support every elected representative by a citizen advisory group (CAG) randomly selected from their electorate and allow the CAG to fire the elected representative if at least 80% of CAG members consider that the elected representative is not meeting the local community’s expectations.

d) Require a consensus for the passing of votes in parliament to be 80% or more.

The end result should be a government more representative of the general population, subject to refreshment monthly. If the politicians are getting things wrong in the public’s view, government’s makeup would quickly change as new pairs of electorates vote over the following months. In the long term, ego-driven politicians should disappear!