What if we could increase voter turnout by 10 percent with one change?

How electoral systems shape voter participation

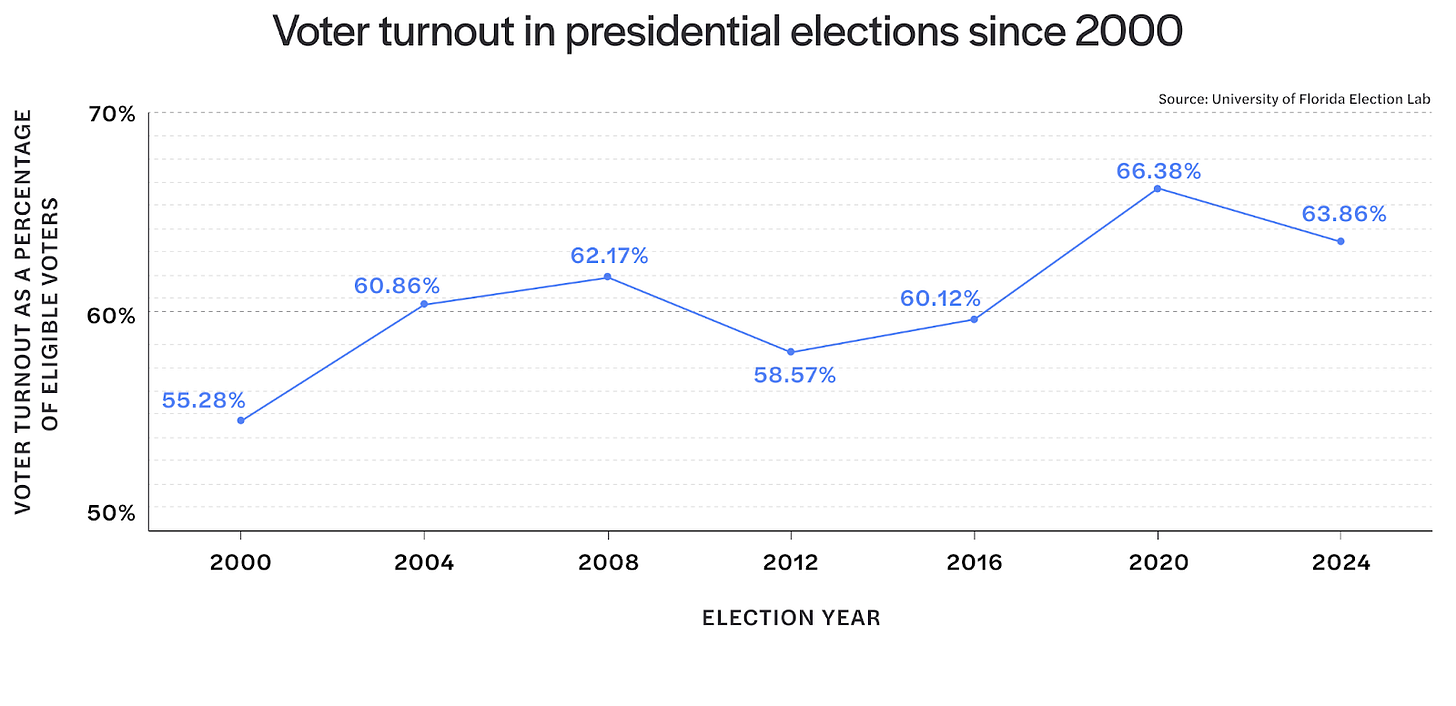

Since 2000, voter turnout in the United States has generally increased 2-3% in every presidential and midterm election with some minor sagging in the mid to late 2010s. The 2024 election attracted unusually high voter interest, with 64% of eligible voters casting a ballot — a number that trails just behind 2020’s record of 66%.

Here’s the thing though: That’s still not very good.

Even in recent elections with relatively high, polarization-fueled turnout, the U.S. lags far behind voter turnout averages among democracies globally. Countries like South Korea, New Zealand, and Germany see 75-85% of eligible voters consistently casting ballots. When compared to the 38 other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member states, the U.S. ranks 30th with an average of 50-60% turnout. Globally, the U.S. is ranked alongside nascent democracies such as Senegal or Kosovo.

This disparity raises fundamental questions about the civic health of American democracy. When turnout is chronically low, as it is in the U.S., it undermines the legitimacy of elected officials, political equality, and trust in government.

With turnout consistently hovering far below peer democracies, we should ask: Why are millions of eligible voters disengaged? And critically, what does the evidence say about whether certain reforms bolster electoral participation?

While much attention has been devoted to the logistical barriers facing voters — from onerous registration requirements to restrictive voting laws — such explanations only go so far in explaining the U.S.’s enduring low turnout problem. At the heart of the issue, according to a growing body of scholarship, lies a more profound structural problem: the design of the U.S. electoral system itself.

Electoral systems have a powerful impact on voter turnout

The winner-take-all system used for U.S. elections is inherently exclusionary. By granting victory to a single candidate in each district, millions of voters are rendered irrelevant.

Consider a congressional race in which Candidate A secures 60% of the vote.

The remaining 40% of voters, though significant, are effectively left unrepresented. In fact, a district with this vote distribution is considered “safe” for Candidate A’s party, meaning that the 40% has no real chance of ever electing a candidate of their choosing. That is, the losing voter group typically knows that they’re going to lose.

Moreover, in an instance like this, many votes for the winning candidate are also inconsequential to the outcome of the election, which is all but guaranteed. Any American who doesn’t live in a swing state or district understands this intuitively.

And that’s a huge portion of the country. Today, under winner-take-all, over 90% of seats in congressional districts in the U.S. are considered “safe” for one party or another.

In part, this occurs because voters of the same party in the U.S. increasingly live near one another — a phenomenon termed “geographic sorting” — causing districts to easily become “red” or “blue.” Gerrymandering — the practice of manipulating district boundaries to purposefully create lopsided districts — does the same.

Our winner-take-all elections rely on single-member districts, which are ultimately to blame. With only a single winner, districts quickly and easily become lopsided — all it takes is a 5-10% margin for a single party to dominate. And single-member districts are uniquely vulnerable to gerrymandering.

Said differently, winner-take-all depresses electoral competition. And, if you look across different elections, voter turnout is closely tied to electoral competition. Why bother turning out if outcomes appear to be forgone conclusions?

This is particularly true for minority voters. Extensive research demonstrates that turnout in the U.S. is lowest among minority populations. In 2018 and 2020, Black and Latino voters each comprised approximately 9% of the voting population, but were 15% and 18% of the nonvoting population. People of color overall make up 30% of the electorate but cast only 22% of ballots. Conventional wisdom holds that voting-eligible citizens of color may abstain from voting because they feel that the dominant parties fail to represent their interests consistently or effectively.

However, an often overlooked factor may also be at play. Burgeoning research indicates that minority voters may abstain from voting because they simply aren’t asked to participate.

In a 2018 study, researchers found that voter mobilization strategies used by both major parties in the U.S. neglect Black, Asian, and Latino voters. These voters are less likely to be courted by candidates because they are more likely to live in “safe” districts where their votes are not decisive in the outcome of the election — another way that the winner-take-all system negatively impacts voter turnout and further deepens racial divides.

Proportional systems produce higher turnout rates

Proportional representation — the main alternative to winner-take-all — dependably produces higher turnout rates. Unlike winner-take-all, proportional systems use multi-member districts and allocate legislative seats based on the proportion of votes each party receives.

In established democracies with proportional systems, voter turnout exceeds that of winner-take-all systems by an average of 9-12 percentage points.

Consider a three-seat district with five candidates. For illustration, imagine the three winning candidates each receive 25% of the vote, and the two losing ones split the remaining 25 percent. In this case, then, 75% of all the votes translate into representation. While stylized, the example illustrates a common feature of proportional representation, where politics are more representative, and the electorate more engaged.

Under proportional representation, more votes count — and turnout increases. In established democracies with proportional systems, voter turnout exceeds that of winner-take-all systems by an average of 9-12 percentage points.

Moreover, while turnout comparisons often focus on wealthy, long-established democracies, this trend holds even when examining a broader range of countries, including newer democracies: Voter participation is generally higher under proportional systems.

Why does proportional representation increase voter turnout?

According to scholars, proportional representation increases voter turnout for three reasons.

First, representation for more voters: In 2023, 8 in 10 Americans believed that their elected officials did not care about their opinions; 7 in 10 reported that the average citizen has little influence on their representatives. Most Americans feel that the government does little to address their most pressing concerns. Under winner-take-all, significant shares of votes often do not translate into seats — or into the policy outcomes voters want. This can leave them feeling that it’s not worth their effort to cast a ballot. A 2017 study by the Pew Research Center found that 30% of unregistered voting-eligible citizens and nearly 20% of registered voters did not regularly vote — in part because they felt that their votes didn’t matter.

Proportional representation, by contrast, awards seats based on the percentage of the vote share each party receives. In turn, more votes tend to translate into seats, and further, into policy outcomes. Proportional systems are better at facilitating the policy outcomes voters want, and in general are known to produce more responsive legislatures compared to winner-take-all. Increased political efficacy — the belief that individual participation can influence political outcomes — is a key factor in driving voter turnout. When voters see that their votes matter, that they influence outcomes and are translated into representation, they are reasonably more likely to participate in elections.

Second, competitive elections: In winner-take-all systems, single-member districts are often dominated by one party, reducing competition and leading to predictable electoral outcomes. Voters are less likely to cast a ballot when the outcome of an election appears predetermined.

By contrast, the multi-member districts used in proportional systems are less susceptible to the geographic sorting that contributes to depressed competition: Even if a district is only 35% “blue,” it may still be competitive when there are more seats in contention. They are also much more difficult (and sometimes impossible) to gerrymander. Proportional representation, with its multimember districts, thus minimizes the distortions of winner-take-all, making elections more competitive and outcomes less predictable.

Using data that tracked changes in voter attitudes over six years before, during, and after the implementation of proportional representation in New Zealand, one study found a nearly 9% increase in the number of voters who reported feeling that their votes impacted the outcome of elections. The same data set reflects a nearly 7% decrease in the number of people who considered abstaining from voting.

Turnout as a function of competition appears especially pronounced among traditionally underrepresented groups. Researchers find a “large gender turnout gap in uncompetitive districts and a small gap in highly competitive districts.”

Following the adoption of proportional representation in Norway, turnout increased overall, but women’s turnout increased at a faster rate than men’s in newly competitive districts. With regard to race, scholars have found that turnout among minority populations is dependent on the size of the population but is likely to increase when elections are more competitive.

Third, party-driven mobilization among minorities: More competitive electoral environments under proportional representation can incentivize parties to engage with an array of racial and ethnic groups, knowing their votes are crucial to winning seats. Additionally, given that proportional representation tends to generate multiparty systems, minor parties that are more responsive to the needs of marginalized voters can offer representation themselves, or encourage other parties to run competitive candidates on their own tickets to secure part of the minority vote share.

Research finds that under proportional representation, parties are more likely to engage in direct outreach to minority populations, which evidence shows increases turnout among minority voters.

This inclusivity creates a sense of efficacy and fairness, as voters feel that their choices directly impact outcomes, fostering broader political participation. Proportional systems correlate with higher rates of political activism, civic group membership, and trust in government — all indicators of robust civic engagement.

As we reflect on the 2024 election cycle, the limitations of the U.S. electoral system are once again laid bare. Even in high turnout elections, such as the 2024 presidential race, nearly 90 million eligible voters abstained.

By comparison, Donald Trump received just under 77 million votes. Republican candidates for the House of Representatives won, cumulatively, 74 million votes. In other words, if “not voting” were a party, that party would likely have won the White House, the House, and the Senate.

This pattern is not simply a matter of apathy, but a reflection of a system that fails to inspire confidence in its inclusivity and fairness. Proportional representation offers a path forward by ensuring that nearly every vote matters and that legislative outcomes reflect the full spectrum of voter preferences. Moreover, as the U.S. confronts broader challenges to democratic legitimacy, embracing structural reform may prove essential in restoring faith in its institutions.

Competition also produces better candidates, and better candidates get more people out to vote.

In Illinois where I once lived they had this odd system for the state state elections which is no longer used. But still it's interesting. Each district elections 3 people. Voters had votes that the could ither it for 3 candidate or split their votes between 2 candidates [1 1/2] votes each] ot 3 votes for one candidate. This usually resulted in 1 person from both parties elected in every district

Eir 3 votes bet