The oldest abuse in human government

Donald Trump and the ‘king’s justice’

“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned… except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.”

— Magna Carta, 1215

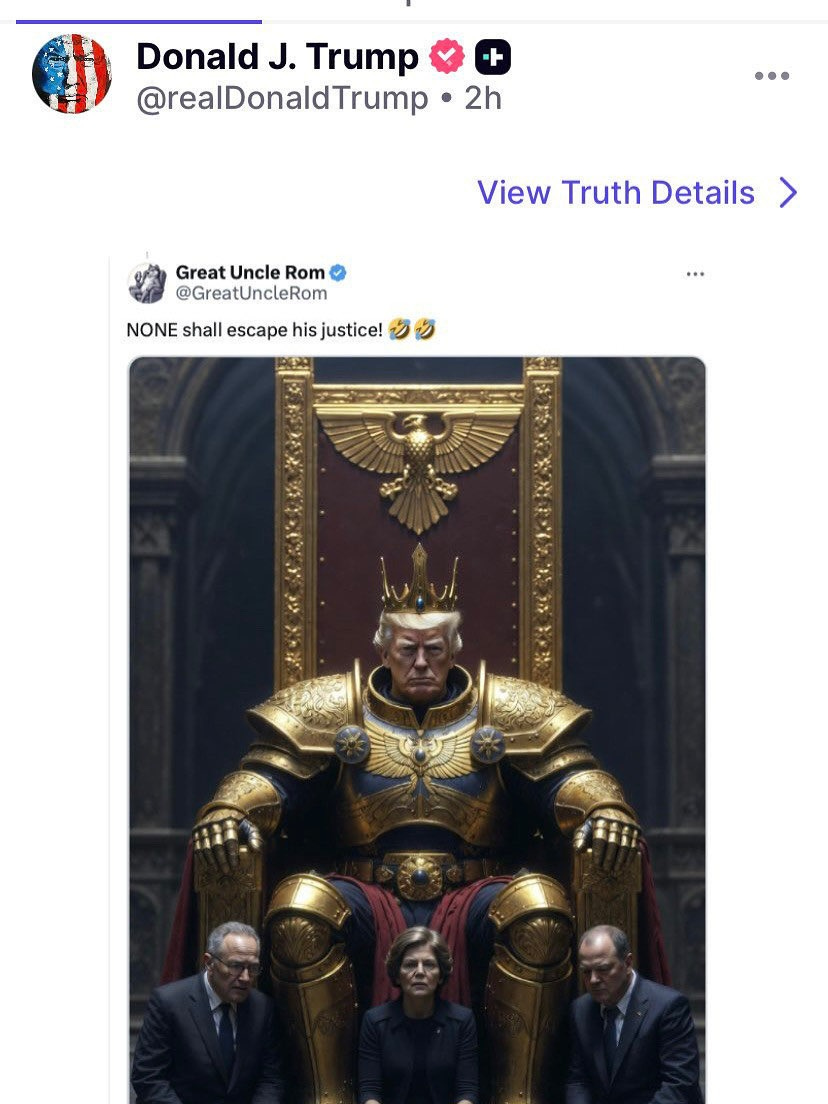

Over the weekend, the president posted an AI image of himself as a king in a golden crown and armor lording over three kneeling Democratic senators: Chuck Schumer, Elizabeth Warren, and Adam Schiff.

The caption: “NONE shall escape his justice.”

In his second term, Donald Trump has claimed an absolute right to direct federal prosecutions and has demanded personal loyalty from government lawyers as he pursues a retaliatory legal crusade against those he perceives as opponents.

A head of state using prosecutorial powers to target their enemies is not a new idea. It is one of the oldest abuses in human government.

For centuries, leaders have sought to wield the law as a personal weapon. And for as long, those who built the traditions on which our legal system is based constructed protections against that — to separate justice from personal rule.

In England, the Magna Carta first articulated the principle that independent law enforcement is a vital protection of individual liberty. Here in America, our Founders put that principle at the heart of our republic from the very beginning, embedding it in a set of constitutional protections.

Over the years, those constitutional checks proved insufficient to constrain power-hungry impulses of presidents who sought to weaponize the law against their opponents, so executive branch policies and statutes have been needed to reinforce the Founders’ vision. The result is a relatively fulsome norm of prosecutorial independence, with all of our overlapping checks and balances against abuse, that is built on a thousand years of Anglo-American legal precedent.

For decades, the consensus in American politics was that these foundational principles must be conserved. That abuses would not be tolerated.

And yet today, Trump’s words and actions in his second term threaten to shatter what was one of the successes of our republican government that set America apart — justice of the law, not of the king. In so doing, his actions mark a reversal of nearly 1,000 years of effort to insulate the awesome power of prosecution from the leader’s whim.

To understand the dangers, it’s worth looking more closely at what got us here and why.

The ‘king’s justice’ and the first attempts to constrain personal rule

Before the rule of law, there was the king’s law. In medieval Europe, the monarch was not merely a head of state; he was the living embodiment of legal authority. The law’s ultimate expression, “the king’s peace,” was not a guarantee of justice but a claim of total jurisdiction. To breach the peace was to defy the king, and whether or not one was protected by the king’s peace — or cast out as an outlaw — remained a potent, personal tool.

This power was systematically abused.

King John, for example, used the royal courts as a personal treasury and a weapon. He charged exorbitant fees to grant, deny, or even delay justice. And he used the courts to bring frivolous charges against barons who dared defy him in order to crush them and seize their lands.

This was not just policy; it was personal vengeance. The most infamous case was that of William de Braose, a former royal favorite. After a falling out, King John demanded an impossible sum from him. When de Braose fled, John captured his wife and son. He had them thrown into a dungeon at Windsor Castle and starved to death.

This was the “king’s law” in practice. It was unpredictable, vindictive, and indistinguishable from the monarch’s personal will.

The first great rebellion against this came in 1215, when English barons, haunted by the fate of the de Braoses, forced King John to sign the Magna Carta. Its famous promise — no imprisonment or seizure of property “except by the lawful judgment of [one’s] peers or by the law of the land” — was a direct response to John’s tyranny. It was a revolutionary attempt to strip prosecution of its personal character. Law would now operate through procedure, not whim.

It was a fragile beginning, but it changed history.

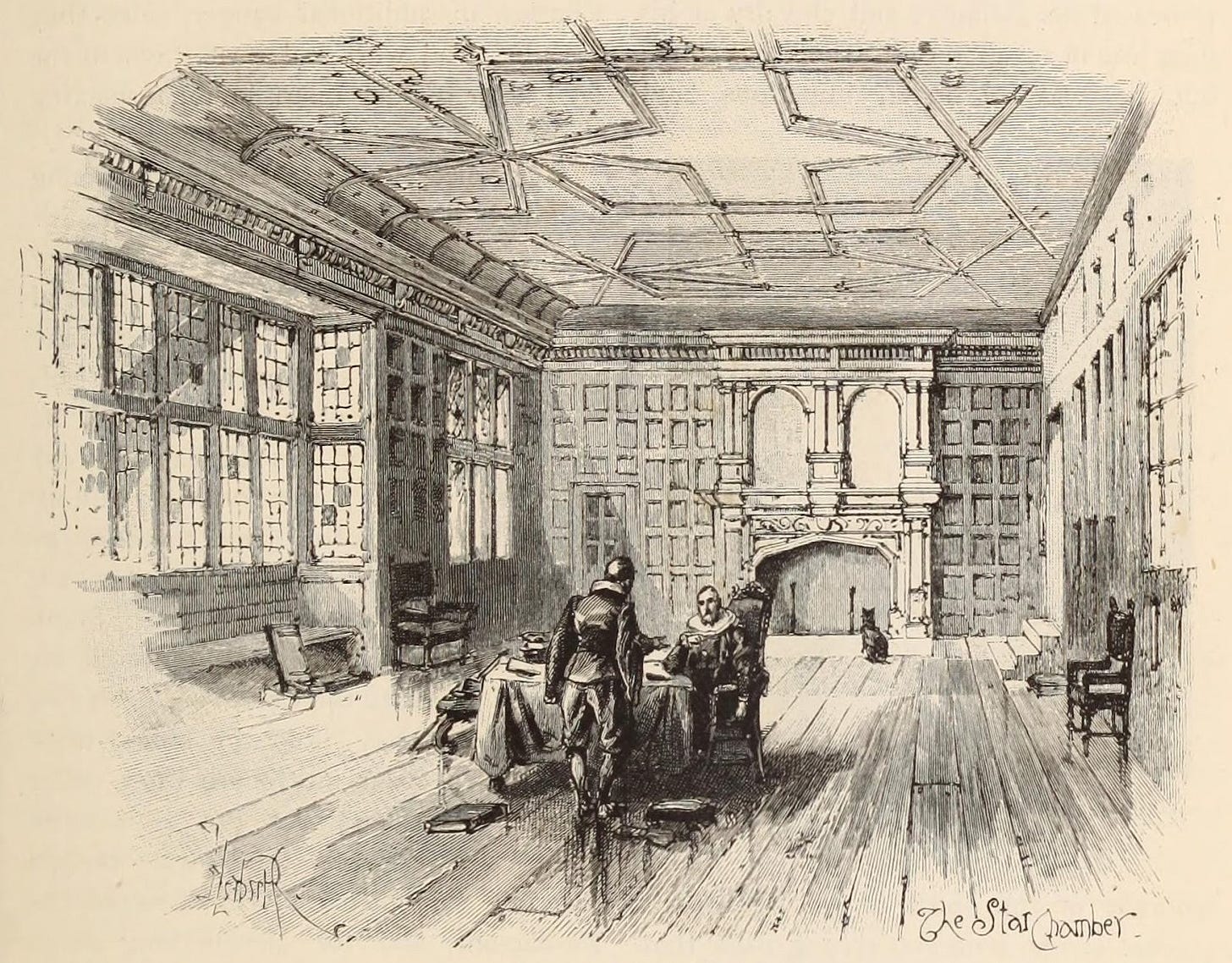

By the 1600s, England’s monarchs had sought to reclaim much of the power taken from them. King Charles I used special courts like the Star Chamber to silence opposition.

One of its victims was William Prynne, a lawyer and Puritan pamphleteer who criticized royal excess. The court fined him £5,000, sentenced him to life imprisonment, and mutilated his ears. His crime was speech.

Parliament revolted against prosecution without law. In 1641, it abolished the Star Chamber, denouncing it as a tool of tyranny. But after the monarchy fell, Oliver Cromwell’s regime repeated the pattern, using tribunals to punish its own critics.

The lesson was brutal and simple: When justice answers to a single will, it becomes indistinguishable from vengeance.

When monarchy returned, James II again dismissed judges who ruled against him and prosecuted opponents under “seditious libel.” His most famous victims were the Seven Bishops, Anglican clerics charged merely for petitioning the king.

Their jury acquitted them, defying royal command — and the crowd outside erupted in cheers. That moment broke James’s authority. Months later, he fled the kingdom in the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

The revolution’s settlement began with the Bill of Rights of 1689, which declared that suspending or executing laws by royal prerogative was illegal. This was followed by the Act of Settlement of 1701, which finally secured judicial independence by mandating that judges would henceforth serve “during good behavior,” not at the monarch’s pleasure.

For the first time, judicial independence was not just a popular demand but an established constitutional principle.

Each of these reforms was a brick in a wall built against the fusion of personal authority and prosecutorial power — a wall upon which our founders would lay more bricks with the creation of the United States.

The American Revolution: Independence from the king — and his prosecutors

When the Declaration of Independence accused King George III of making judges “dependent on his will alone,” the Founders weren’t just lodging a new complaint — they were echoing the crisis under James II. When they protested the “swarms of officers” and the infamous “Murder Act,” which allowed royal officials to be tried in England rather than the colonies, they were remembering the unaccountable power of the Star Chamber and the danger of justice administered by a distant, hostile will.

The new American Constitution was intended to place the principles of the Magna Carta, the 1689 Bill of Rights, and the 1701 Act of Settlement at the heart of the new republic. To address the excesses and failures of our monarchical forefathers from the outset. The Founders built its architecture as a direct, point-by-point rebuttal to centuries of royal overreach:

Separation of powers: To ensure the person who enforces the law (the president) could not also write or judge the law, breaking the dangerous concentration of power held by a king or a “lord protector” like Cromwell.

Life tenure for judges: To permanently solve the problem of monarchs like James II dismissing judges who defied them.

The grand jury: To ensure no citizen could face a “prosecution without law” unless a body of their fellow citizens first found the evidence credible — a direct barrier against arbitrary charges.

The right against self-incrimination: To forever ban the inquisitorial tactics of the Star Chamber, which had relied on forcing men like William Prynne to testify against themselves.

Freedom of speech and press: To finally abolish the state’s power to silence critics through “seditious libel,” the very charge used against both Prynne and the Seven Bishops.

Trial by jury: To guarantee that a citizen’s fate would be decided by their peers, not a distant official or a biased prerogative court.

Prohibition of bills of attainder: To make it impossible for a legislature to simply declare a person guilty without a proper trial — the ultimate tool of political vengeance.

The Take Care Clause: To create a duty that the president serves as a good faith steward of the law, barred from abusing power to punish enemies, and not as an unaccountable embodiment of state power.

These constitutional measures were not abstractions; they were firewalls, built from the scar tissue of history and designed to ensure that justice could never again be indistinguishable from vengeance.

America had done something that no other country on earth had managed: Built a country on the rule of law, not the rule of man. The question would then become whether we could live up to these principles in practice.

From kings’ courts to the Justice Department: the modern turn toward institutional independence

What the Founders did not do was create a Department of Justice. Nor did they imagine an independent prosecutorial institution insulated to a larger degree from presidents. The office of attorney general was established in 1789, but it was originally a part-time post with a small remit: advising executive branch officials on legal issues and representing the government before the Supreme Court.

As federal law evolved and numerous prosecutorial offices were established, especially in the aftermath of the Civil War to implement reconstruction, Congress created the Department of Justice in 1870 to centralize federal law enforcement under one roof.

The DOJ wasn’t designed as a medieval-style check on the sovereign. But it did represent a further step in the American Constitutional vision of a government designed to serve a charter, not a king.

This independence, however, was a cultural ideal, not a legal guarantee. The fundamentally anti-Constitutional temptation to use the law as a personal tool and political weapon and shield never disappeared. The department’s culture had to be consciously built and fiercely defended. Presidents from both parties interfered at times, and the early department lacked firm internal guardrails. The idea that, to uphold the principles of the Constitution, the DOJ must necessarily resist partisan use of prosecutorial power took decades to fully emerge and even longer to take root.

A turning point came in 1940 when Attorney General Robert H. Jackson articulated what would become a foundational ethic: that prosecutors wield immense power over “life, liberty, and reputation” and that their duty was to “seek truth and not victims,” to serve the law rather than faction. Jackson did not claim prosecutors were free from political oversight — he was himself an appointee of the president — but he insisted that professional norms must restrain the impulse to use prosecution as a political weapon.

The idea that the department must not become a president’s personal charging machine captures the ethos Jackson championed. He was describing a culture of internal restraint, a commitment by career prosecutors to the integrity of the law even when the law’s enforcement touched the powerful.

That norm, though never fully codified in statute, was simply a recapitulation of constitutional principles for the twentieth century. But the lack of codification would remain a weakness for decades to come.

Watergate and the formalization of independence

By the 1960s, the norm Jackson described was under strain. Presidents and their attorneys general still had significant influence over prosecutorial decisions. The appointment of the president’s brother, Robert Kennedy, as attorney general raised questions about whether the nation could truly expect independence from the department’s political leadership.

Then came Watergate. President Nixon ordered the DOJ to target political opponents and to shield his allies. When the department’s special prosecutor began investigating him, Nixon demanded his firing. The “Saturday Night Massacre” — in which Attorney General Elliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus resigned rather than carry out the order — crystallized the issue: Unchecked presidential direction of prosecutions was incompatible with the rule of law.

It’s important to note that while Nixon’s abuses were partisan in nature, the backlash was not. Watergate was a watershed moment because, when tested, Americans and political leaders from both parties stood up for America’s founding principles — even when doing so meant negative political consequences for a president from their own party. The bipartisan message was clear to future generations: Prosecutorial independence is one of those bedrock American values worth conserving.

Indeed, the public backlash was enormous, and for the first time, reforms codified the independence that Jackson had framed as a professional ethic.

President Ford’s attorney general, Edward Levi, established the Office of Professional Responsibility in 1975 to investigate misconduct within the department. President Carter’s attorney general, Griffin Bell, issued the first formal memo limiting and structuring communications between the White House and DOJ about specific cases. This memo — a tradition that has been reaffirmed by every subsequent administration before this one — was a direct response to Nixon’s “backchannel” efforts to politicize investigations.

Carter also signed the Ethics in Government Act of 1978 which, among other things, codified the need for an independent special prosecutor to investigate high-level executive branch officials. (Notably, this reform recognized the potential need to be able to prosecute high level officials, including even presidents, as it came in the wake of Watergate. It insisted, however, on a special further layer of independence to do so.)

These measures did not eliminate presidential authority. They did not render the DOJ a fourth branch of government. But they did something historically significant: They built a modern firewall to prevent prosecution from becoming an instrument of personal or partisan retaliation. This was the American system’s equivalent of the many historical attempts — from the Magna Carta to the Act of Settlement — to separate legal judgment from personal will.

In other words, the truly robust version of DOJ independence is relatively new. The principles it embodies are older than the American republic itself. It was deliberately constructed because earlier safeguards, by themselves, proved insufficient.

The limits and realities of the jury system

None of this, however, is self enforcing.

Even the firewalls that are beyond the direct control of the president, like the right to indictment and trial by jury, are not failsafes. In practice, each layer of protection is prone to slippage — slippage that an abusive leader can exploit.

Grand juries, for example, which are supposed to prevent wrongful charges from ever being brought, are ripe for prosecutorial abuse, leading to the idea that they are famously willing to “indict a ham sandwich,” as the saying goes.

Trial by jury, the ultimate check, has also been notoriously unreliable when swayed by public passion or prejudice. For example, throughout the Jim Crow era, all-white juries routinely acquitted white defendants for the lynching and murder of Black citizens, a pattern exemplified by the 1955 acquittal of Emmett Till’s murderers, who later confessed to the crime. And even today, juries are often prone to biased, wrongful convictions. A 2022 report from the National Registry of Exonerations found that innocent Black people were seven times more likely to be wrongly convicted of murder compared to innocent white people.

In the modern era, prosecutors use the “trial penalty” — the threat of a much harsher sentence at trial versus a plea — as overwhelming leverage. This has effectively erased the jury trial from the federal system. According to the Pew Research Center, as of 2022, over 97% of defendants in federal criminal cases plead guilty or didn’t see trial, never availing themselves of their Sixth Amendment right.

This system is so coercive that it traps the innocent. The same National Registry of Exonerations report found that 26% of all known exonerees — people later proven to be completely innocent — had pleaded guilty to a crime they did not commit.

And even upstanding members of society can often be found to have committed technical violations if an unscrupulous prosecutor is committed enough to singling them out for persecution. As the Soviet secret police chief Lavrentiy Beria is reputed to have said, “Show me the man and I’ll show you the crime.” In such cases it is often impossible to access or produce the evidence necessary to meet the incredibly high bar for winning an affirmative vindictive prosecution defense, at which point juries provide little further protection.

Of course, these problems exist even when prosecutorial decisions are in the hands of independent bureaucrats rather than a political leader (hence the need for and existence of norms and other checks there as well), but when a head of state engages in prosecutorial abuse it sets a norm that trickles down to infect the whole system.

The best our system has been able to achieve in terms of fairness has depended on the full and overlapping suite of these protections, built up over centuries — producing a system approaching fairness but still far from perfect.

And even when the system does ultimately check abuses, the ordeal itself becomes the punishment. For the rare, well-resourced defendant who can fight all the way to a “not guilty” verdict, the financial ruin, public stigma, and years spent under threat of prison is a sentence of its own.

For these reasons, a system that allows the president to order prosecutions based on personal animus or partisan motive cannot be redeemed by the possibility of a later, costly acquittal. The ordeal is the punishment. And for the tens of thousands of citizens without the fame or fortune of a high-profile target, the threat is even more potent.

And significant social costs are borne by those not ever charged. Indeed, the threat of mere prosecution acts as a powerful chill against anyone who might consider exercising their freedoms by criticizing the president or taking other lawful actions that might subject them to the leader’s ire.

So, for example, even though the indictments of James Comey and Letitia James have been dismissed (for now, as the dismissals are without prejudice to charges being refiled), they have already had part of the desired impact in serving as a warning to anyone else who might seek to hold the president accountable that they do so at their peril.

The king’s justice returns — the re-personalization of power

This brings us to the present moment. The second Trump administration has taken a direct aim at the post-Watergate settlement — the modern firewall meant to separate the president’s political interests from prosecutorial decisions. To cite just a few examples:

April 9, 2025: The president signed a presidential memorandum (sometimes referred to as an executive order) directing the DOJ and Department of Homeland Security to investigate the activities of former DHS officials Chris Krebs and Miles Taylor. Both were outspoken critics who had previously refuted the president’s claims about election integrity.

June 5, 2025: The president ordered his administration to investigate former President Joe Biden for his executive actions, arguing he was too mentally impaired to do the job, using the power of the presidency to initiate an investigation without stated evidence or criminal predicate.

Sept. 20, 2025: The president posted a public message on social media addressed to “Pam” (Attorney General Pam Bondi) demanding that she and the DOJ “prosecute” and “serve justice” against his perceived political enemies, specifically naming former FBI Director James Comey, New York Attorney General Letitia James, and Senator Adam Schiff.

And these examples do not include orders the president may have given privately, such as directing the DOJ to purge from its ranks anyone involved in prior investigations of or prosecutions of the president himself or those he considers his allies.

These abuses do not amount to a claim that America is returning to medieval monarchy or that Trump wields unilateral power resembling Charles I or James II. Courts remain independent. Juries still sit. Procedural rights still exist. Much of the constitutional inheritance remains intact.

The concern is simpler, more precise, and in some ways more alarming: For the first time in American history, a president has openly claimed that justice is an extension of his will — a rejection of not only what the Founders envisioned but of the thousand years of effort since the Magna Carta to reject such an approach. (Recall the meme he posted that opens this piece for a window into how he views his role.)

The White House–DOJ separation memo, one modern attempt to enforce constitutional principles that was honored by presidents of both parties for half a century, has been abandoned. Public calls for investigations and charges based on personal grievance have become a governing posture rather than a breach of etiquette. The expectation that career prosecutors should be insulated from political retaliation — once a hard-won achievement — is now contested from the top.

This is the modern form of what the Founders recognized and rebelled against as “the king’s justice”: not dungeons or attainders, but the idea that the machinery of law enforcement can be steered by personal will.

The distinction matters. In every era, the fight was not about whether rulers had any involvement in prosecutions. They always did. The fight was over whether the ruler’s personal desire to punish critics or spare allies could decide how the law was used. It reflects a repeated lesson: When leaders use prosecution as a vehicle for retribution, the rule of law erodes, even if the legal forms remain in place.

Why this matters beyond any one man

This thousand-year history is not a morality tale nor a partisan story. It is a story of this nation having finally achieved the long-sought goal of building a structure that could protect the majesty of the law from the baser instincts of an increasingly less virtuous political class.

The people who built these firewalls — from the barons at Runnymede to the reformers after Watergate — were not naive. They knew the temptation to use power as a weapon is permanent. They also understood that the very nature of freedom itself depends upon not being subject to the arbitrary and retaliatory personal whim of those in power. And they knew that the only defense is a system that protects everyone, even those you despise.

If a president discards one of those layers — particularly the most recent and deliberately constructed one — the entire structure becomes more fragile. And once a president uses prosecutorial direction as a political weapon, the precedent does not disappear when he leaves office. It becomes available to the next administration, and the next, turning what was once unthinkable into an accepted tool of governance.

A Department of Justice that can be aimed by one president at his enemies can, by the next president, be aimed at his. This is the simple, brutal lesson of Oliver Cromwell, who, having defeated a tyrant, adopted his tools.

Some argue that America has long seen prosecutions of political figures — Don Siegelman, IRS scrutiny of Tea Party groups, the cases against Trump himself. But this conflates two fundamentally different things: a legal system that can reach powerful people and a powerful person seeking to command the legal system for personal ends. The former is essential to the rule of law. The latter is its undoing.

Indeed, the prosecutions of Trump were handled by a special counsel operating under rules designed specifically to keep partisanship out of charging decisions. The White House went out of its way to avoid involvement; at the same time, the president’s own son faced prosecution, underscoring the independence of the process. That is not weaponization; it is exactly the kind of system the post-Watergate architects sought to build.

That inheritance reflects the hard-won understanding that the moment justice becomes personal, freedom becomes contingent.

When a modern president demands prosecutions of political opponents, he is trampling on a thousand years of Anglo-American legal tradition and utterly disregarding the intent of the Founders. He is giving in to ugly human tendencies that republican government exists to confine.

And he is attacking an American inheritance of independent law enforcement that — to invoke the ultimate principle of conservatism — is worth conserving.

The more I learn of what the founders did for us the more I am awestruck.

Fantastic. I wish there was a means to make 320M read this plus force it down DJT (Russel Vought, etc.) throat to be consumed whole.

Their insatiable need to rule by fist must be quenched before the whole system comes down. Much work still ahead.