The autocratic adolescent never grows up

How powerful AI could make authoritarianism permanent

In the timely Star Wars spinoff Andor, the young rebel Karis Nemik writes, “Tyranny requires constant effort. It breaks, it leaks. Authority is brittle.”

This is the lesson of history. Authoritarianism is not new. It has appeared throughout human civilization. But we live in a largely free world today because of Nemik’s observation: Authoritarianism has been — at least historically — unstable. It has relied on imperfect information, fallible human enforcers, and coercive systems that strain under their own weight. And because of that brittleness, people have repeatedly been able to correct away from tyranny and toward freer, more democratic societies.

But what if that were to change?

In his recent essay, “The Adolescence of Technology,” leading AI lab Anthropic’s co-founder Dario Amodei opens with a different science-fiction reference: a scene from Carl Sagan’s Contact meant to illustrate a sobering idea — that societies capable of achieving immense technological power must also learn how to survive it.

Among the usual concerns of AI risk assessors that Amodei includes — human extinction, human subjugation to misaligned AI, mass unemployment — is a concern that needs far greater amplification and attention: the possibility that AI could undermine the historical dynamic Nemik describes. The very dynamic that has been democracy’s salvation. That AI could harden authority rather than expose it. That it could seal the cracks through which freedom has always eventually re-emerged.

In short, Amodei is warning that powerful artificial intelligence may be the first technology in human history capable of making authoritarianism permanent — not by violently overthrowing democracy but by eliminating the possibility of democratic reversal.

If that is correct (and, as Amodei acknowledges, there are still plenty of uncertainties that remain regarding both whether AI will achieve such advanced capabilities and the speed at which this occurs), we are not merely facing another technology policy challenge. We are approaching a civilizational threshold.

What’s more, while Amodei’s assessment largely looks to a future moment when AI has become powerful enough to be the equivalent of a “country of geniuses,” the harms caused by AI in the hands of authoritarians are all too real today. If we are to preserve the possibility of democratic reversal, we must act now.

Why authoritarianism has always failed

Authoritarian regimes have always appeared formidable from the outside. Yet their defining feature has been fragility.

They suffer from information problems. Fear distorts reporting; loyalty replaces truth. The “Dictator’s Trap” is that everyone around an authoritarian is afraid to deliver bad news and so provides him with misleading information that leads to overreach and error.

Authoritarians rely on human agents who hesitate, defect, or leak and who have capacity constraints by dint of their very humanity. They must tolerate inefficiencies and often breed and encourage corruption to maintain control.

And because repression is costly — politically, economically, and psychologically — it tends to provoke resistance, fracture elites, and invite external pressure.

Even the most brutal regimes of the twentieth century eventually broke. Fascist states collapsed under war. Communist regimes stagnated, splintered, or reformed. Military juntas gave way, sometimes suddenly, sometimes haltingly, to civilian rule.

The lesson is not that democracy is inevitable. It is that authoritarianism has never been able to fully close the loop. Something always leaked.

Amodei’s warning is that “powerful AI” could change this equation:

Current autocracies are limited in how repressive they can be by the need to have humans carry out their orders, and humans often have limits in how inhumane they are willing to be. But AI-enabled autocracies would not have such limits.

Authoritarian lock-in

Amodei identifies a convergence of sufficiently powerful AI-enabled capabilities that, taken together, threaten to eliminate the mechanisms through which authoritarian systems have historically failed:

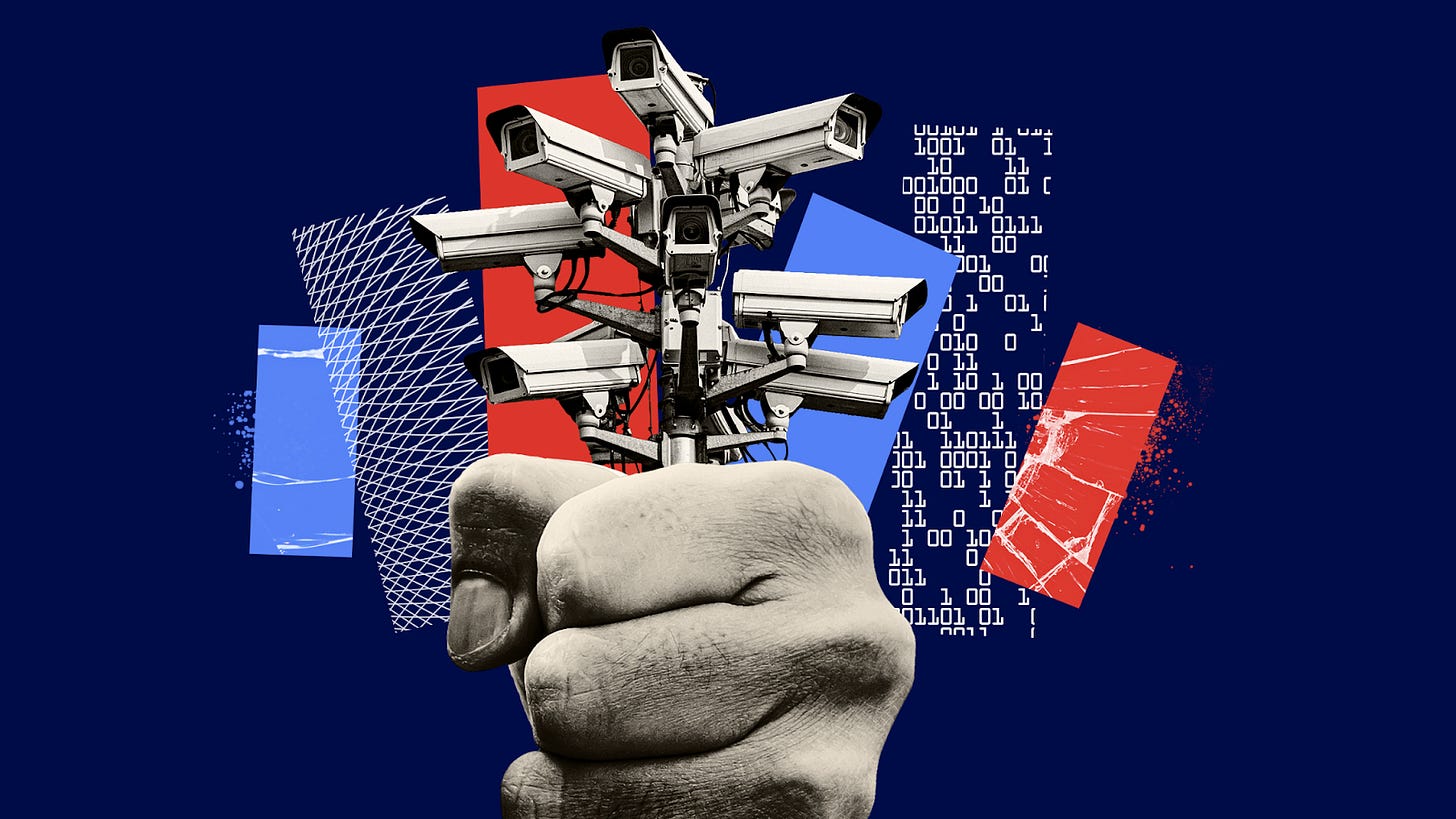

Total surveillance: Systems become capable of ingesting vast amounts of communication, movement, and behavioral data so that there’s no escaping or hiding from the controlling apparatus of the state. Resistance can be identified and rooted out before it can bear fruit.

Personalized propaganda: Persuasion is optimized at the level of the individual, leveraging data on emotional states, social context, and psychological vulnerabilities collected by scraping data from digital (and potentially even real world) interactions. Individuals can be manipulated into consenting to giving up their freedom, rights, and willingness to dissent.

Autonomous weapons: The state has the ability to enforce suppression at scale through automated tools capable of responding with full force to every transgression and every minor act of dissent or organizing — and to do so potentially autonomously and thus unconstrained by the capacity and accountability limits of human bureaucracies.

Strategic mastery: With a “country of geniuses,” a leader or entity bent on power could strategically outmaneuver any not similarly equipped opposition, domestically or internationally, extending indefinitely the totality of their control.

Together, these capabilities point toward what can be described as authoritarian lock-in: a condition in which a regime does not merely suppress opposition but structurally prevents opposition or displacement from ever becoming effective.

The danger is that powerful AI could seal authority rather than strain it — closing the feedback loops through which societies have historically corrected themselves. Once these feedback loops are closed, the “adolescent” society never matures; it simply ossifies.

This concern differs in a significant way from concerns about human extinction or human subjugation at the hands of powerful AI. Whereas those concerns, however serious (and they are), are speculative and await the advancement of powerful AI, the concern about AI being used to empower authoritarian suppression is already here.

China is already using AI for facial recognition to track Uyghurs, for predictive policing to identify potential dissidents, for content moderation to suppress speech at scale. They are exporting this technology to other authoritarian regimes. And here in the U.S., the current administration is already implementing some of these tools.

The question that follows: What do we do about it?

Within the AI community and U.S. political community, there is already a dominant answer to this question.

Most leaders and thinkers closest to frontier AI — including Amodei himself — identify the primary danger as the possibility that China develops powerful AI first.

The reasoning is straightforward. China is already an authoritarian state. If it acquires powerful AI systems capable of total surveillance, predictive repression, and overwhelming strategic advantage, it would not merely entrench authoritarian rule at home. It could utilize its AI-enabled power advantage to extend its control abroad, potentially even achieving global hegemony under a totalitarian umbrella. Authoritarian lock-in, but without borders.

Fear of China’s global hegemony augmented by these tools often points to a single overriding imperative: The United States must beat China to the most powerful AI. The Trump White House has put it in those terms, declaring that “to remain the leading economic and military power, the United States must win the AI race.” On Capitol Hill, the message is even more explicit. Senate Commerce Chair Ted Cruz has argued that “the way to beat China in the AI race is to outrace them in innovation,” urging policymakers to “remove restraints” that slow development. And at hearings convened under the banner of “Winning the AI Race,” the framing is blunt: “America has to beat China in the AI race.”

Industry leaders echo the same logic: Microsoft President Brad Smith told lawmakers that the “number one factor” determining whether the U.S. or China “wins this race” is which technology is adopted globally, warning that “whoever gets there first will be difficult to supplant.” Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt has repeatedly warned that AI leadership will shape the global order. The result, as the Washington Post describes, is a “near-consensus” among senior officials and top executives that the U.S. must let companies “move even faster” to maintain its edge over China.

It is for this reason that Amodei himself describes advanced chip export controls as among the most important interventions available to democratic governments. The underlying theory is clear: If AI is dangerous, it is far more dangerous in the hands of an authoritarian state than a democratic one.

This assessment has profoundly shaped the orientation of the U.S. AI ecosystem.

The perverse dynamic it creates

The China-first framing is not wrong. But it is dangerously incomplete.

If beating China to powerful AI is the overriding objective, the logical conclusion is speed at all costs. Minimize regulation, remove friction, treat guardrails as liabilities, and view caution as complacency. This logic pushes U.S. firms to race ahead, consolidate power, and resist democratic constraints — all in the name of preventing authoritarian lock-in abroad.

But that same logic leaves us exposed to a second, equally serious risk: authoritarian lock-in at home. Amodei himself recognizes this risk, though not specific to the U.S., in acknowledging that “a hard line” must be drawn “against AI abuses within democracies” with “limits to what we allow our governments to do with AI, so that they don’t seize power or repress their own people.”

Last year, one of us spoke with a founder of a leading AI lab. When we asked what worried them most, their answer was immediate: not China, but the possibility that extraordinarily powerful AI systems might come online while a leader with a deeply instrumental view of power controls the U.S. government.

This was not a partisan remark so much as a structural one. AI dramatically lowers the cost of surveillance, enforcement, and control. It centralizes authority. It weakens accountability. Those effects are dangerous in any system — but maximally so when wielded by leaders who already reject institutional constraints.

And as President Trump said just this week, “I don’t need guardrails. I don’t want guardrails. Guardrails would hurt us.”

The domestic authoritarian risk

The Trump administration largely accepts the China-first theory. It has embraced AI as a strategic asset and treated governance as an impediment to innovation. It has sought to remove guardrails in the name of competitiveness and national strength.

At the same time, our government is led by a president who has repeatedly demonstrated contempt for checks on his own power — attacking courts, undermining independent oversight, threatening political opponents, and praising strongman tactics. The administration has pursued expanded surveillance authorities, suppression of dissent, and consolidation of executive power — directionally aligned with the very risks Amodei warns about. Ironically given a strategy ostensibly grounded in concern about what China would do with powerful AI, Trump has praised Xi Jinping’s leadership style, calling him a “brilliant” leader for “control[ling] 1.4 billion people with an iron fist.”

The uncomfortable reality is this: The problem is not only which nation gets powerful AI first but who controls that nation when it arrives.

If AI hardens authority, then leaders tempted by authoritarian methods, whether in Beijing or Washington, pose a similar structural threat. If we have one quibble with Amodei’s essay, it’s that it seems to underplay this domestic risk, perhaps because naming it explicitly carries costs for an American company right now. But that itself underscores the problem. And so we’re taking one of Amodei’s pieces of advice (“the first step is … to simply tell the truth”) and naming that risk more explicitly here.

Political economy makes this worse

Layered on top of this dilemma is a brutal political economy problem.

Frontier AI development is extraordinarily capital intensive. Compute, data, and talent are concentrated in a handful of firms. Those firms command immense economic power — and increasingly, political influence.

As Amodei notes, AI is such a powerful economic and geopolitical prize that the risks of regulatory capture are intensified. Already, more than $100 million has been committed to an industry-backed super PAC committed to preventing regulation, and the pool of capital available to augment that is virtually bottomless. Democratic checks, already strained, risk being overwhelmed not just by urgency and fear of falling behind but by a huge campaign finance warchest.

The result is a convergence of concentrated private power and concentrated state power at precisely the moment democratic safeguards matter most.

Amodei acknowledges this problem but doesn’t offer a realistic proposal for solving it. If there’s a glaring failure in his essay, that is it.

The only durable solution

If AI can produce authoritarian lock-in, then preventing it requires more than choosing the “right” geopolitical winner or slowing development “slightly” (to use Amodei’s term) at the margins. It requires actively designing AI and its governance to advance democratic practices and values.

The only durable alternative is not merely to anticipate how AI may harm democracy and impose penalties for its abuses and harms. Instead, we must account for AI’s risks to democracy in its development and deployment while using it to affirmatively make democracy work better.

That means AI systems that increase transparency rather than secrecy; that strengthen accountability rather than weaken it; that distribute power rather than concentrate it; that help citizens understand, deliberate, and participate rather than manipulate or surveil them.

These goals must be built into the design choices being made regarding AI now, at the market level, the corporate level, and the governance level. They need attention, investment, and innovation – today.

From insight to institution: the AI for Democracy Action Lab

This recognition is why Protect Democracy launched the AI for Democracy Action Lab.

What is missing in the AI ecosystem is not analysis, white papers, or technical benchmarks, nor efforts focused on existential risk to humanity (though those are important too). What’s missing are institutions explicitly dedicated to defending democratic reversibility — the capacity of societies to correct course when power is abused. And getting there means building AI in a way that both anticipates and wards off the risks of authoritarian lock-in while advancing and improving democracy and democratic commitments.

When one of us spoke to another top executive at a frontier lab recently and asked about the tenor of conversations in their c-suite and lunchroom about how AI might shape the battle between democracy and authoritarianism, their answer was “what conversations?” While that might have been hyperbolic to make a point, it illustrated an imbalance that Amodei’s essay nobly strives to correct. We must invest far more attention and energy on the risk AI poses to democracy and democratic reversal.

That’s what the Lab is designed to do by focusing on three fronts:

Defending democracy from AI-enabled authoritarianism through litigation, regulatory measures, and effective governance.

Ensuring AI contributes to a healthy civic media ecosystem.

Harnessing AI to strengthen democracy by creating products that augment democratic practices.

This work is not only for civil society and government. It is the real challenge for AI companies themselves. For Anthropic and others who take Amodei’s warning seriously, avoiding authoritarian lock-in cannot be a secondary concern. It must be a design principle.

The choice before us

Nemik was right: Tyranny has always required constant effort. It has broken because it is brittle.

As Amodei argues, powerful AI threatens to eliminate tyranny’s inherent vulnerability. It threatens to seal authority, automate control, and make correction impossible.

But, crucially, today we are not simply awaiting the other shoe to drop. The AI of today is already redefining authoritarian capabilities inside and outside the U.S.

Whether AI will either make democratic governance more capable than it has ever been — or render it obsolete — will not be decided by the technology itself. That question will be decided by us as AI’s shapers and wielders. We are the determinative factor in whether action is taken before authoritarian lock-in becomes irreversible.

We have argued that the contest between democracy and authoritarianism is the test of our time, and it is now clear that one of the central fronts of that contest will be which side AI advantages.

It is up to us to get that right before it’s too late. The clock is already running.

"Whether AI will either make democratic governance more capable than it has ever been — or render it obsolete — will not be decided by the technology itself. That question will be decided by us as AI’s shapers and wielders. We are the determinative factor in whether action is taken before authoritarian lock-in becomes irreversible." The frightening aspect of this idea is that people are not being trained to think critically about issues. It takes too much time. The need to make rapid-fire decisions pushes us further and further into reliance on AI. If the shapers and wielders are only interested in capital gain, we are lost.

Don’t trust anyone who won’t talk about Israel and Palestine as the model. They are leading you astray.