History’s lessons for reform advocates

Why (and how) to keep diverse pathways to proportional representation open

Picture this: Electoral reform is having a moment in the United States. From California to Ohio, reform proposals are gaining steam. A bunch of city governments — including some, big notable ones — have adopted proportional representation for local elections. Reformers are eyeing state and national elections next.

But we’re not talking about 2025 or 2026 or 2027. We’re talking about 1925.

It’s true! Proportional representation has a long and rich history in the United States. We just mostly forgot about it.

Read more: Proportional representation, explained.

Between 1915 and 1950, 24 U.S. cities — including New York City, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Sacramento, and Long Beach — adopted proportional representation. The reform wave swept across the country.

But then something went wrong.

In 23 of those 24 cities — all except for Cambridge, MA — the reform was repealed within a decade or two. The reasons why are hotly debated. But in any interpretation, both the successes and the failures of past generations of reformers provide an important chapter in history to learn from for advocates of all types.

So. How do we harness the successes of the past and avoid the failures to build sustainable momentum towards national change?

First, an electoral systems refresher

To debate the history, we need some wonky details on how different versions of proportional representation work.

In concept, proportionality is simple — the legislature should reflect the proportions of the electorate. If a third of voters have similar interests, they should be represented by a third of the seats. As John Adams put it in 1776:

“[The legislature] should be in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large. It should think, feel, reason, and act like them.”

But in practice the mechanics are trickier. You need a way to translate percentages of the vote into actual humans elected.

To achieve proportional outcomes — where seat shares roughly approximate vote shares — most democracies rely on “party list” or “slate” systems, where voters select a party, often in addition to the voter’s preferred candidate. Based on its share of the vote, the party gets to seat a proportionate share of its candidates. You’re often voting for two things at once: how many seats your preferred party gets and which specific candidate you think should get one of that party’s seats. Simplified, these ballots look like this:

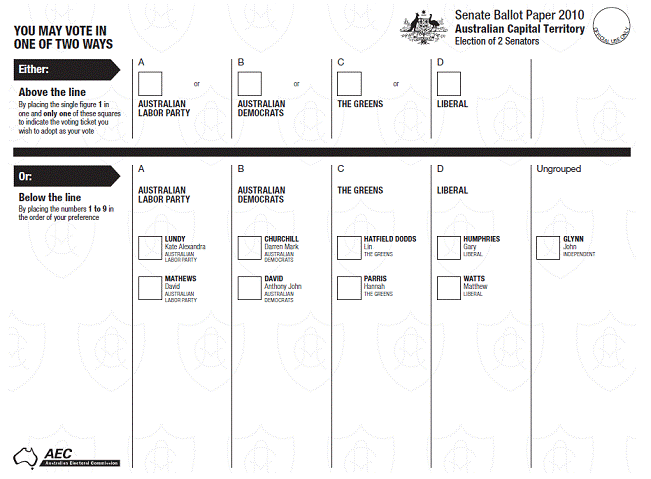

Some places — Ireland, Scotland, Australia, and Malta — use a ranked choice voting system called the “single transferable vote” (STV) where voters rank their preferences and candidates are either eliminated or elected until only a set number of candidates remain, with results proportional to the share of votes’ cast. But unlike with party-list systems, candidates are not always grouped by party on the ballot and voters have the option to rank candidates across party lines. In the U.S. context, those ballots look something like this instead:

Read more about how this works via FairVote here.

Many reformers have landed on this version — often called “proportional ranked choice voting” in the U.S. — as the preferred form of proportional representation for the U.S. There are a number of important reasons:

It’s more candidate-centric (less party-centric) in a country and culture where elections have traditionally focused on candidates and political parties are often widely distrusted.

It easily allows for independent candidates who don’t want to be grouped together with a party, which is appealing to many Americans (a growing number of whom do not affiliate with either major party).

It works for both partisan and nonpartisan elections (roughly 70% of all local elections —and 85% of all city elections — in the U.S. are nonpartisan).

It follows logically from the single-member district version of ranked choice voting, which is gaining steam in states and cities (including, again, New York City) and works for single-winner races like mayors and governors as well, allowing voters to have a consistent voting experience across all races.

Some advocates believe that by allowing voters to rank individual candidates, it provides a tool for communities with shared interests to elect their preferred candidate(s) directly, even if the group of voters might otherwise be split between multiple parties or split between multiple candidates of the same party.

STV was also the version of proportional representation used in all 24 of those 20th century cities. (Mostly it was because of the nonpartisan elections thing. Like today, widespread frustration with partisan politics was a powerful force that reformers could tap into in the Tammany Hall era.)

The million-vote question — how do we succeed where the last reform wave failed?

Proportional representation is once again having a moment. A growing number of cities are adopting STV and some are exploring party-based proportional reforms as well. All of which makes learning the lessons of the past more urgent than ever.

Why, after gaining such a foothold in the United States, was proportional representation almost universally repealed? And how can reformers avoid the same fate today?

In other countries, proportional representation seems to be a one-way ratchet — once adopted it’s almost never repealed. Whether list or STV, once proportional representation abroad has been legalized, neither the voters nor the politicians seem willing to let go of it. But in the United States it was repealed 96 percent of the time.

The traditional narrative of why is simple: STV was repealed because it worked. Political scientists such as Douglas Amy, David Farrell, and Kathleen L. Barber emphasize that these adoptions provided for proportional representation of electoral minorities at a time in American political history when there was widespread, bipartisan opposition to the election of racial, ethnic, and ideological minorities. As Professor Amy argues:

“[STV] was rejected because it worked too well. STV worked too well in throwing party bosses out of government, bosses who never relented in their attempts to regain power. More importantly, STV worked too well in promoting the representation of racial, ethnic, and ideological minorities that were previously shut out by the first-past-the-post system. The political successes of these minorities set the stage for a political backlash that was effectively exploited by opponents of STV.”

As Professor Barber notes in her work, “The election of two Communist Party members in New York City in 1945, and of African Americans in Toledo and Cincinnati, figured prominently in repeal campaigns.” Like many aspects of American political history and development, racial progress is often followed by retrenchment.

In this telling of history, proportionality itself largely spurred the backlash — a fact that likely would have followed the adoption of any particular system of proportional representation.

But, recently, a more critical narrative has emerged. In a 2022 book, More Parties or No Parties, political scientist Jack Santucci argues the opposite: STV failed because it didn’t work.

Santucci argues that STV outsources coalition management directly to voters. Instead of empowering politicians to build a potential governing coalition and present it to the voters for support — as happens in more party-based systems — STV relies on voters to build a coalition at the ballot box. And because voters can rank candidates based on any number of dimensions — party, ideology, race, ethnicity, gender, religion, etc. — it may be less clear to parties and candidates alike what those coalitions are.

The core problem, Santucci argues, is “vote leakage,” which he describes as a ballot that ends up counting for a candidate from one party (say, a Republican), even if the voter ranked a candidate from another party above them (say, a Democrat). While the ability to rank across party lines may be one of the features STV advocates like about the system and may sound intuitively nice — encouraging bipartisan behavior and such — Santucci argues that in practice it muddied the water of which faction was actually supposed to represent that voter. According to Santucci:

“Some leakage is normal. For example, votes might leak from Working Families to the Democratic Party, or from the Libertarian Party to Republicans. Such leakage can reflect explicit coalition deals or simply that these parties are ideologically similar.

But leakage is a problem when it upsets the main divide in a party system—for example, when it goes from Democrats to Republicans (or vice versa), ‘good government’ to ‘old machine’ (or vice versa).”

In other words, Santucci argues that STV introduced a chaos factor that leaders from both major parties grew to dislike.

He looked at rates of vote leakage across different cities over time and found that increasing rates of vote leakage immediately preceded cross-partisan repeal efforts. In his words, as vote leakage increased, “both major parties agreed that STV was problematic. It came to hurt both of them at once.”

Put more bluntly: The critique is that reformers (either deliberately or accidentally) tried to destroy political parties in favor of a system that made coalitions more difficult and elected individual candidates based on personal appeal.

So, the political parties turned around and destroyed the reform.

What this all means for reformers

One does not need to “take sides” in the debate to think that both scholars offer important lessons for advocates of STV and list systems alike.

Advocates of list systems might think Santucci has a compelling historical argument and that party-based systems will be less prone to cross-partisan efforts at repeal. Advocates of STV might subscribe to Amy, Barber, and Farrell’s account, believing that any system of proportional representation would have faced white, cross-partisan backlash at the time, and think STV still has the best practical chance of winning over the American people for all the reasons above.

Or one might not be confident in either of those possible positions.

Either way, if you believe — like we do — that a more proportional politics in general is the necessary response to our democracy crisis (and that tapping into our national history of proportional representation can help us do so!), then it makes sense to remain open to a diversity of strategies and reforms. After all, this is a question that our democracy can’t afford to get wrong.

So four lessons from this historical debate to take forward:

One: Focus on the end goals — pluralism and representation

Every reform is an instrument to an outcome, not an end in itself. Even as we argue and debate and experiment, let’s not miss the forest for the trees. American democracy is under threat because a calcified two-party system supported by winner-take-all elections are advantaging extremists and has put an unpopular autocrat back in the White House.

Anything that healthily introduces more representation, pluralism, multi-dimensionality, coalition building, and party competition into our politics is a positive development. Reformers are united by many shared goals, even if distinguished by diverging strategies. It’s going to take a broad coalition to move major change, so the more we can find areas to collaborate and lift each other up, the better.

Two: Stay experimental

Because we don’t know exactly how different reforms will interact with the particular idiosyncrasies of American politics, we should be building a diverse portfolio of reform efforts with a reasonable degree of experimentation among proven systems as an explicit goal. Over-investment in any specific reform strategy, be it party-list or STV or otherwise, risks catastrophe if the bet goes bad. Alternatively, every reform that tries something slightly different gives us more data about how proportional representation works in the real, 21st-century United States.

Reformers should explore party-list proportional representation in situations where it makes sense, in parallel to the STV efforts already showing impressive traction.

Plus, this is a big, diverse country. The version of reform that works — and, indeed, the problems reform seeks to solve — in California may not be the same as in Wyoming (where, coincidentally, conservative reformers have proposed a list-based system for the state legislature). We should welcome this difference.

Three: Find ways to channel — not resist — parties and factions

Political scientists almost unanimously agree that political parties are a necessary feature of a healthy democracy, as much as many Americans dislike them (the parties, we mean, not the political scientists). They’re the basic organizing function that keeps politics from descending into chaos. So one key question for reformers is this: How can we tap into widespread frustration with the parties as they are today to enact reform while proposing ways to help them function better in the future to sustain reform? Party-list advocates can learn from the adoptions of the Progressive Era just as STV advocates can learn from the repeals.

One bit of good news on this: Party-list and STV systems aren’t actually mutually exclusive. People who find candidate-centric reforms like STV politically attractive can incorporate party lists or slates into the ballot design itself.

For instance, Australia uses a modified version of STV for Senate elections that allows voters to either rank individual candidates or to rank their preferred party. This seems to largely solve the problem of vote leakage (with most voters choosing to rank the parties “above the line”) while still giving voters the option of picking individual candidates and allowing independent candidates.

Even more marginal changes to STV can help thread this dynamic. For example, allowing allied candidates to be grouped together on the ballot or including party or slate labels on the ballot can help make coalition boundaries clearer and help voters more easily rank the candidates that collectively represent their interests.

Four: Beware the election reformer’s dilemma

Finally, regardless of what happened back in the early 20th century, it’s worth approaching reform with a degree of humility regarding what will work, what won’t, and why. This is in part due to “the election reformer’s dilemma”:

The people who are most excited about electoral reform at the outset often approach politics from a different perspective from the voters the reform is intended to serve.

Almost by definition, those of us who are excited about electoral reform on its own merits are not anywhere close to the average voter. Election reformers tend to be far more politically engaged than the majority of the electorate. Many have more free time to engage in politics, or even count reform or politics as a full-time job. Some of us may follow the latest research produced by political scientists (or be political scientists ourselves). And some of us may be personally willing — even excited — to vote in multiple elections a year and have fairly detailed preferences and political views, including on individual candidates, ballot issues and so on.

In short, a “policy first” reform strategy in almost any jurisdiction is going to be inherently vulnerable to blind spots unless and until the coalition of support in that jurisdiction grows and expands to meet and include more of the people most affected by the proposed reforms: the voters themselves.

If electoral reform is going to succeed, we’re going to have to center voters, constituencies, and parties, along with their concerns, politics, and desires. We might be surprised to find which reforms end up resonating with different communities as reform continues to gain traction. This may be a list system in some communities or a ranked system in others. Reformers have much to learn from those we seek to serve.

We should continue to lean into uncertainty and learning, not shy away from it.

So, as we proceed down the possible path to better electoral systems, we should be humble about questions of reform design, experimental in our approach, and quick to consider new evidence or contrasting ideas.

Hopefully by learning lessons from both the successes and the failures of the past, we can finally deliver on the century-long effort at transformational reform and the promise of a more responsive, healthier, more secure democracy for future generations.

But just in case…

If you are reading this in 2125 and the American electoral system is still stuck in mucky dysfunction: Whatever strategy it is we used — try something else!

In Jack Santucci’s book "More Parties or No Parties," and also in several of his articles, he gamely and quite reasonably tackled a difficult historical question: “Why was STV repealed in two dozen cities in the middle of the 20th century?” As a core part of his answer, he explained his theory behind “vote leakage” and “What relevance does vote leakage have for reform efforts today?”

As someone who has studied, researched and written (in books and articles) about this myself, going back many years, I thought Jack’s “vote leakage” conclusion was an interesting thesis. But ultimately it is unconvincing. I know from personal experience – having been in the trenches of electoral system reform for three decades – that the reason a reform wins or loses is a matter of a number of factors. There is never one reason. Jack’s “vote leakage” addition to previously identified factors – mainstream intolerance of elected minority perspectives, complexities of counting ballots by hand, defeated anti-reformers waiting for the right political moment to repeal, insufficient time for the public to get use to STV (I note that in his table 5.1, of the couple dozen STV cities, nine of them used STV for five years or less, and five more for 12 years or less) – all of these explanations are credible to me, especially in combination with each other in a variety of mixes, depending on the city. And those reasons are not so easy to quantify.

There are several weaknesses in the “vote leakage” argument. Jack tried to tie this to the behavior of political parties in each city. And yet in all of these cities, with the exception of New York City, they were nonpartisan elections. Certainly in nonpartisan elections, political parties still attempt to exert their influence. In San Francisco where I lived for 30 years, and before that in Seattle, which are heavily Democratic cities, the Democratic Party endorsement and slate card mailer is a significant force. But when the voter walked into the voting booth in these STV cities, they did not see party labels on the ballot, they saw only candidate names. While Jack drew a conclusion that the political parties became opposed to STV because they did not see it serving their interests, what about the voters who voted to repeal? What were their reasons?

I’m certain party leaders’ antipathy is to some degree true, but not for the reason that is implied in Jack’s argument. The answer is far simpler: the anti-reformers wait for their chance to repeal. Full stop. And it’s not just political parties that have that attitude, BTW, but also certain business leaders, oftentimes newspaper editors and media personalities, status quo NGOs, stubborn election officials, and a whole host of American curmudgeons who are against change (“That’s not what the Founders intended!”). This attitude has repealed not just STV, but also campaign finance reform, in recent years vote-by-mail reform, early voting, voter ID and more. Because of this attitude, the size of the U.S. House is still stuck at 1910 levels. Many people are afraid of change.

And that’s just political reform, the anti-reformers also have repealed reforms targeted at economic insecurity, or gender parity and much more. There is nothing mysterious or hidden about this dynamic, the anti-reformer attitude has always been with us. It does not only emanate solely from political parties and their disaffections. And it did not just manifest with STV in a handful of cities. It is everywhere, all the time. It is the ground on which political reformers walk.

Certainly, in my experience, the dominant political parties – both Democrats and Republicans -- are inherently conservative organizations. They generally like the rules that elected them, especially true of the individual incumbent legislators, who of course their votes you need to pass or protect your reform. Which raises another possible explanation for the repeal of STV that Jack’s book did not adequately deal with: according to Kathleen Barber and others, STV broke up political machines in most of these cities. And that led to unremitting hostility from the old guard that has lost its dominance. Under this alternative thesis, it's not just a matter of "vote leakage" in which party leaders saw some voters give their lower rankings to candidates not to their liking (such as candidates from another party). It's more that these political leaders lost real political power, and they waited for their chance to repeal, and fanned other factors -- racial intolerance, Red Scare, perceived complication of a new system of ranked ballots, perceived complexity of hand counts, the reasons varied from city to city -- to push repeal. Compared to those very real dynamics that involve very human factors and motivations, i.e. craving for (return to) power, everyday voters’ simplistic understanding of politics, and more, "vote leakage" feels like a pretty thin reed upon which to rest the case for all those repeals.

Jack has written that his thesis of vote leakage is the one that best fit the "patterns in the data" – but his data was very limited. No one knows what the leaders of repeal thought in the various cities, why they thought it was so urgent to repeal. There are no interviews with these leaders, no diaries of their thoughts that we know of, though there are a few observations and comments from various quarters. But nothing definitive. We have no polls or focus groups from that time period, asking the public its views, teasing out subtleties of opinion – was STV just too complicated? Were the long hand counts a downer? Was the old guard striking back against any and all reform? If so, those explanations undermine Jack’s exclusive thesis about STV being repealed because of dissatisfaction among party leaders over inability to control their voters' votes. If the voters had been greatly satisfied with STV, it would not have mattered what the party leaders thought or did. I think we have to be careful not to draw too strong of a conclusion from such a limited data perspective that Jack presents in his book.

Certainly there's some interesting and suggestive evidence in his data, and some amusing anecdotal observations. I would love to have read more stories from those eras in Jack’s book. Such a colorful time and cast of characters. More of the "who said/did what" type of history would have been fascinating, as well as I suspect illuminating. But we don’t get much of that from Jack’s book, and the evidence he does present does not seem conclusive. There are too many alternative explanations for repeal that he would have to eliminate as influential, one by one, in order to raise the profile of his "vote leakage" theory. Look at the list that I mentioned in my second paragraph. Jack did not really address any of those other possible reasons for repeal in his book. I was surprised at how little he addressed Kathy Barber's thesis, which in my reading of her book was quite strong.

Which is fine, that wasn't Jack’s focus. But it does illustrate the narrowness of his focus as a limitation. As I wrote above, there is never ONE reason for repeal (unless there is some scandal that happened, like in San Francisco when Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone were assassinated and in a bizarre narrative twist, the assassinations were blamed on district elections). Jack has certainly added something interesting to the discourse of "what happened" so many years ago. But at least in my view, his research and data does not settle this question of why all these repeals happened.

And to the extent that I accept vote leakage as a real phenomenon, I don't see it being such a significant factor that it is very relevant to the election system reform movement today. Yes, the political parties are often opposed to this kind of structural change. No one knows that better than Rob Richie and I. We knew that before Jack’s book was published, because we have been fighting Democrat and Republican obstructionism for decades. That's nothing new.

In addition, when you approach this from another angle, one person’s “vote leakage” is another person’s "coalition building" and what others call "voter choice." Of course there is going to be vote leakage, as Jack has defined it, in STV elections. That's SUPPOSED to happen. That's a feature, not a bug. To Jack and others, these apparently are negatives. To me and many others, these are positives.

In short, Jack took some rather interesting research that he conducted, admirably churning thru old election records and such, and has shoehorned this data into a questionable thesis that he (and others) have used to graft this data onto a defense of the importance of political parties in the modern day. I don’t see the connection as strongly as Jack and others do. I don’t think he/they have sufficiently made their case. And besides – who exactly are they arguing against, or trying to disprove? Does any serious person actually think political parties should go away, or be abolished? Or are not still extremely powerful and fundamental organizations in the US political system? This strikes me as being a bit of a strawman argument.

Certainly Jack’s book has found its audience among some enthusiasts, and as a fellow author I congratulate him. As myself and others have said, it’s a big country and there’s room for trying different PR methods. As someone who ran the first STV campaign in the US in decades in the 1996 campaign in San Francisco (we lost, 44-56%), and who ran other successful campaigns for RCV/IRV in various cities, I would personally welcome any passage and implementation of a Party List PR system (open or closed), anywhere in the United States.

Superb explanation of history that may illuminate a way forward. Thank you Ben!