If Congress doesn’t pass a funding bill by midnight tonight, the government is going to shut down.

In the past, shutdowns have been a blame game, with various actors across the White House, the Senate, and the House of Representatives pointing the finger at each other. By definition, when different parties fail to reach an agreement there’s at least some responsibility to go around.

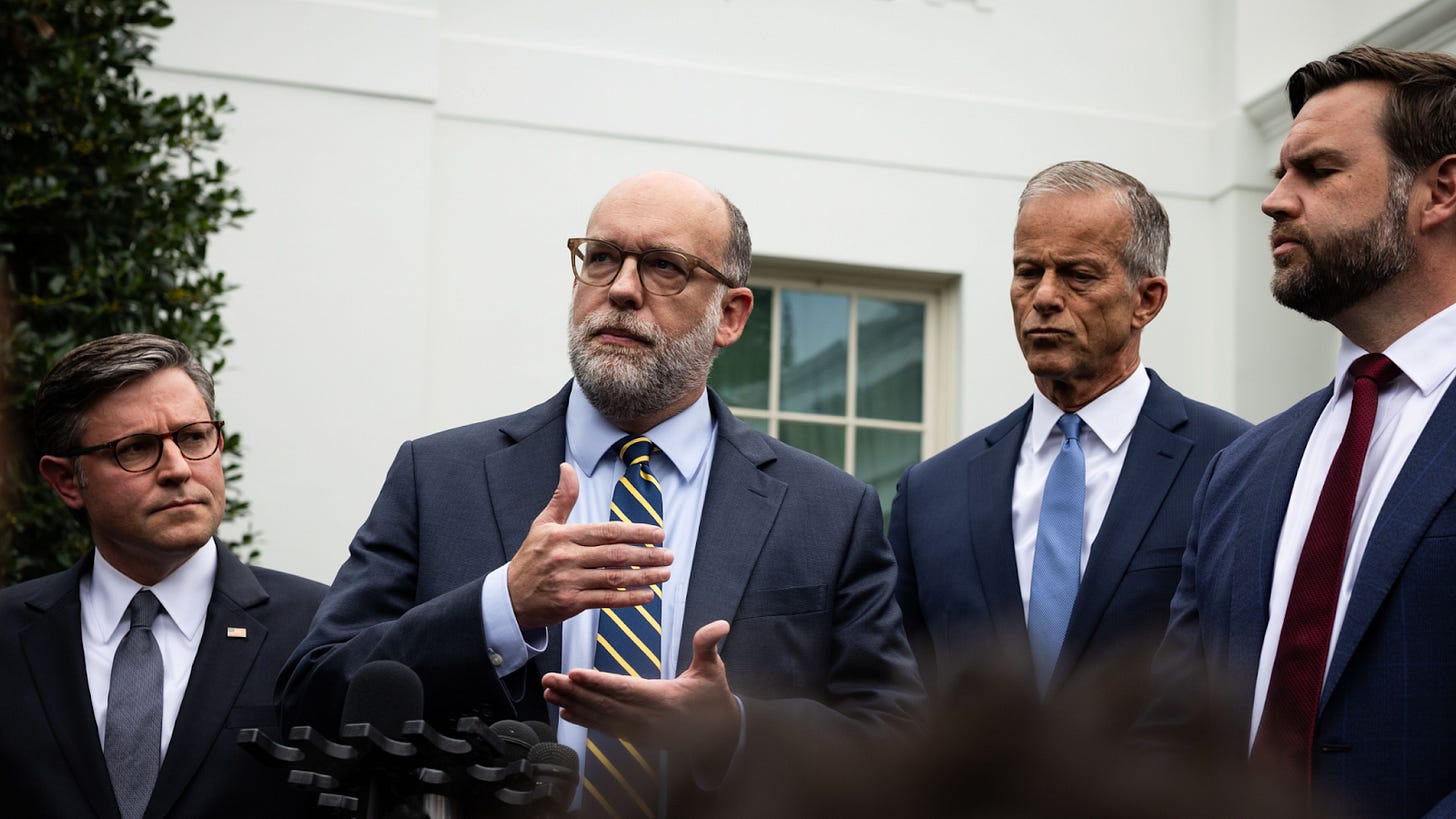

This time though, the blame really does seem to fall on one person, and one person alone: White House budget director and Project 2025 architect Russell Vought. (If his name sounds familiar, it might be because The New York Times just called him “the man behind Trump’s push for an all-powerful presidency.”)

Imagine you and your toddler are playing a game of “keepy uppy” with a balloon. Your toddler grabs the balloon, intentionally pops it — and then asks why you stopped playing the game. (Parents: We’ve all been there.)

That’s more or less what Russ Vought has done to the appropriations process.

To explain why, it’s going to take a little Government Funding 101. Stick with me — the parenting analogy keeps going.

No doubt you’ve heard it before: Article I of the Constitution grants Congress the power of the purse. That means that it’s Congress’s job to pass legislation that spells out what the government will spend money on and how much. To do this, the House and Senate have to pass a law that says how much money the government has to spend and what they are supposed to spend it on.

And then it’s the executive branch’s job to spend it.

If the Congress doesn’t pass such a law by the end of the fiscal year (Sept. 30), then a lot of the things the government does day-to-day suddenly have no funding — from lifesaving cancer research to national parks. That’s what we’re facing right now.

Why we have the appropriations process

For the first two centuries of our country, Congress was mostly concerned with making sure agencies did not spend more than what the law gave them — because, it turned out, agencies were terrible at sticking to their budgets.

In 1870, Congress tried to curtail spendthrift agencies by passing a law that made it illegal for agencies to spend more than Congress gave them. But that law alone didn’t fix the problem. So Congress created the apportionment system, which tasked the president with giving agencies the money that Congress set aside for them a little at a time so the agencies stick to their budgets.

Let’s go back to our toddler who popped the “keepy uppy” balloon. You decide to take him to the party store to buy a replacement balloon. If you walk into the store and tell him he can spend $3 on any color small balloon he wants, odds are he’ll come back asking for something way more expensive, like a giant $15 dinosaur balloon, and say, “Mommy, Mommy, I want that. Give me the money I need for that.”

That’s basically what agencies were doing to Congress for 200 years — budget nerds call it “deficiency appropriations.” Agencies spent their money too fast and then went to Congress asking for more — over and over again.

And that’s one of the reasons why the law is so strict — that when the money runs out at the end of the fiscal year on Sept. 30, the government gets shut down. Congress has to give the executive branch more money before they can spend more.

The president’s job is to spend the money — nothing more or less

In the 1970s, President Richard Nixon tried to defy Congress by doing the reverse — instead of spending more money, he tried to spend less than what Congress passed in the law. That’s called an “impoundment.”

Read more: The myth of presidential impoundment power.

The toddler equivalent would be if your kid got angry that the store didn’t have a dinosaur balloon, so he threw the money and himself on the floor. Basically, impoundments are the “take your marbles and go home” of federal budgeting. And we all understand big feelings, right?

But Congress’s power of the purse requires the president to spend appropriations — even if he disagrees with them.

As Charles Dawes, the first director of the Bureau of the Budget (the precursor to Vought’s post), wrote in 1923:

Much as we love the President, if Congress, in its omnipotence over appropriations and in accordance with its authority over policy, passed a law that garbage should be put on the White House steps, it would be our regrettable duty, as a bureau, in an impartial, nonpolitical and nonpartisan way to advise the Executive and Congress as to how the largest amount of garbage could be spread in the most expeditious and economical manner.

The law doesn’t allow the president to just not spend money Congress has given him. Courts made that clear to Nixon when time after time they forced agencies to spend money he tried to impound.

It’s not unlike a parent telling their toddler, “I’m sorry we can’t get a dinosaur balloon, but we still need to buy a balloon if we’re going to be able to keep playing ‘keepy uppy.’”

Congress was so angry about Nixon’s impoundments that watching him lose in court wasn’t enough, they went a step further and passed a law, the Impoundment Control Act (ICA), making clear that the president has three choices when it comes to laws that spend money.

The ICA allows presidents to a) spend the money, b) delay spending the money and ask Congress if that is OK, or c) ask Congress to cancel the spending with a new law. (Notice that none of these options is “make a unilateral decision to give the money back.”)

For half a century, those rules have been the bedrock upon which Congress and the president negotiate spending laws — laws which are almost always bipartisan. Even when one party has control over the government, as the Republicans do now, they still need some Democratic votes to pass spending bills into law.

Read more: The historical fiction behind Musk & Vought’s cuts.

Those rules are what make the appropriations process like a game of “keepy uppy.” Sometimes the balloon goes in the direction of Democrats, providing more spending for their priorities, and other times Congress hits the balloon towards programs Republicans favor. But playing by the rules, both parties work to keep the balloon floating, and both parties get a chance to hit the balloon and send some funds towards things they — and their constituents — care about.

How Russ Vought broke the budgeting process

In case it wasn’t clear, Russ Vought is the toddler who popped the balloon, ending the “keepy uppy” game of the appropriations process.

First and foremost, Vought refuses to spend funds passed by Congress that he disagrees with — the equivalent of popping the balloon. Remember, this kind of refusal to spend money (impoundment) is why Congress passed the ICA. Impoundments are illegal: Neither the Constitution, federal case law, nor American history support Vought’s claim of an inherent presidential power to impound.

Now Vought claims he has found a way to “comply” with the ICA while still impounding funds without Congress — by submitting a request to Congress to cut the funds so late in the fiscal year that the funds expire before Congress has a chance to consider the request.

Vought calls this form of impoundment a “pocket rescission,” but the Government Accountability Office, law professors, members of Congress, and former budget staffers all agree that pocket rescissions are just unlawful impoundments by a different name.

Read more: Past pocket rescissions are not precedents for power Vought claims.

To make matters worse, Vought refuses to face the reality that even in a government controlled by a Republican president and Republican Congress, as long as the filibuster stands, funding bills need bipartisan votes to become law. Vought has consistently spoken with complete contempt for bipartisanship and makes no bones about believing that he and President Trump have sole authority to decide how much money gets spent and on what — Congress be damned.

Back in July, Vought publicly declared, “The appropriations process has to be less bipartisan.”

True to form, last week Vought attempted to strong-arm Democrats into caving by threatening a new round of mass firings of government workers in the event of a shutdown — instead of, you know, promising that he’ll follow the law and spend funds that Congress requires him to.

Budgeting can’t be about one man

Politicians and experts from both major parties have publicly criticized the way that this White House has broken the appropriations process.

Republican Senator Susan Collins, who is the chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, has called Vought’s budget chicanery “unlawful” and stressed the importance of the bipartisan Congressional appropriations process.

Rep. Steve Womack, an Arkansas Republican and senior GOP appropriator, put it best:

If you’re a Democrat — even just like a mainstream Democrat — your predisposition might be to help negotiate with Republicans on a funding mechanism. Why would you do that if you know that whatever you negotiate is going to be subject to the knife pulled out by Russ Vought? (Emphasis mine.)

Womack asks the right question. If there are no guarantees that the White House will actually spend the money on the priorities passed by Congress, why would Congress work with them to pass a budget?

Every legislator has a stake in the budget. Federal funding supports important programs in every community in every state. That’s why legislators care so much about this whole game of “keepy uppy.”

The game, however, no longer works as it used to. Even if a legislator secures funding that’s important for their district, Russ Vought has claimed the right to cut it after the fact. So voting to avert the shutdown just confirms his power to back out of any deal. Voting “aye” may keep some parts of the government open — the ones Vought supports — but it no longer gives members of Congress any guarantees that the funds they secure in an agreement will actually get spent.

If the government shuts down tonight, a lot of people will be pointing fingers and arguing that congressional Democrats let the balloon drop.

If we’re looking for someone to blame, though, the focus should really be on the guy who popped the balloon.

Very helpful article and analogy.

This is great. Now we all know that the Democrats are the real adults in the room and need to insist that the law be followed! Thanks 🙏